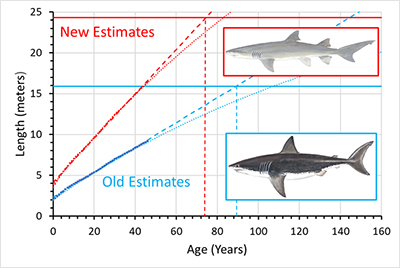

Fossil remains of the giant shark Otodus megalodon have been found in Miocene1 and Pliocene2 rock layers, which ICR scientists interpret as having been formed during the Genesis Flood.3 Paleontologists recently revised the estimated adult body length for megalodon upward from 15.9 meters (52 feet) to 24.3 meters (80 feet). Based on considerations of swimming efficiency, they concluded the megalodon’s body was probably more elongated like that of a lemon shark (see figure) rather than stocky and bulky like that of a great white.4,5 This megalodon took a long time to skeletally mature, and delayed maturation is often associated with greater longevity in living animals.6

Organisms typically undergo rapid juvenile growth which slows down as the creature approaches maturity. Researchers sometimes collect length-versus-age data for a population of sharks to estimate the average growth trajectory for that shark. In theory, such growth curves can also be constructed for extinct fossil creatures, using growth rings in fossil vertebrae. The disk-like part of the vertebra contains growth rings that can be counted, not unlike tree rings.

As the juvenile shark grows rapidly, the ring spacings are relatively far apart. As growth slows down, the spacings become increasingly narrow. When constructing the growth curves, researchers generally assume that the width of each band represents the additional length which the shark grew during the year. They can then use this information to estimate the shark’s total body length over time.

A megalodon vertebra from Belgium has 46 well-preserved, widely-spaced growth rings.1 Under the assumption that each growth ring represents a year of growth, this was a 46-year-old juvenile megalodon that was taking a long time to mature. And there are at least two other examples in the conventional technical literature of large, slow-growing fossil sharks.7–9

Slow-growing sharks found in Genesis Flood deposits? This should resonate with Bible-believing Christians. Genesis 5 strongly suggests that humans in the pre-Flood world experienced both extreme longevity and delayed sexual maturation (and likely skeletal maturation, too) compared to modern-day humans.10 It seems very likely that the same would have been true for pre-Flood animals.

It’s possible to fit standard von Bertalanffy growth curves to these data points.11 Taken at face value, both the original and revised growth curves (curved blue and red dotted lines in the figure, respectively) imply the megalodon would have taken about 500 years (!) to reach 95% of its adult body length.1,5 However, because these data points essentially lie along a straight line (see figure), any growth curve obtained from these data will be highly uncertain.

To obtain a more conservative age at maturity, I extrapolated the juvenile growth rate to estimate the time for this megalodon to reach its adult body length. Under the assumption that it had a body shape like that of a great white shark, it would have taken more than 89 years. Under the assumption of a body type more like that of a lemon shark, it would have taken more than 74 years (see figure). These are extremely conservative estimates because they ignore the slow-down in growth that occurs over time. Because such a decrease would only increase the time for the shark to reach maturity, these ages are minimum values. Despite the downward revision in age at maturity, this is still a slow-growing shark. For comparison, North Atlantic great white sharks take about 33 years to reach 95% of their adult body length.12

At this time, we probably don’t have enough data to get a firm estimate of the megalodon’s age at maturity or lifespan. However, today’s large (seven-meter-long) Greenland shark has a lifespan of at least 272 years and possibly more than 500 years. Its age at sexual maturity is estimated at 150 years.13 Given that this megalodon was conservatively more than two to three times longer than the Greenland shark, an age at skeletal or sexual maturity measured in centuries seems entirely plausible. And as in the case of the Greenland shark, such a prolonged age at maturity would likely have been accompanied by an even longer lifespan—just as one might infer from Genesis.14

References

- Shimada, K. et al. Ontogenetic Growth Pattern of the Extinct Megatooth Shark Otodus megalodon – Implications for Its Reproductive Biology, Development, and Life Expectancy. Historical Biology. 33 (12): 3254–3259.

- Boessenecker, R. W. et al. 2019. The Early Pliocene Extinction of the Mega-Toothed Shark Otodus megalodon: A View from the Eastern North Pacific. PeerJ. 7.

- Clarey, T. 2019. Rocks Reveal the End of the Flood. Acts & Facts. 48 (5): 9.

- A Longer, Sleeker Super Predator: Study Paints More Accurate Picture of Megalodon’s True Form. Phys.org. Posted on phys.org March 9, 2025, accessed March 13, 2025.

- Shimada, K. et al. 2025. Reassessment of the Possible Size, Form, Weight, Cruising Speed, and Growth Parameters of the Extinct Megatooth Shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae), and New Evolutionary Insights into Its Gigantism, Life History Strategies, Ecology, and Extinction. Palaeontologia Electronica. 28 (1): a12.

- See discussion in Hebert, L. III. 2023. Allometric and Metabolic Scaling: Arguments for Design...and Clues to Explaining Pre-Flood Longevity? Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. 9, article 18.

- Giant ‘Teenager’ Shark from the Dinosaur Era Identified from Vertebrae Remains. Phys.org. Posted on phys.org April 23, 2020, accessed May 30, 2024.

- Jambura, P. L. and J. Kriwet. 2020. Articulated Remains of the Extinct Shark Ptychodus (Elasmobranchii, Ptychodontidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Spain Provide Insights into Giantism, Growth Rate and Life History of Ptychodontid Sharks. PLoS ONE. 15 (4): 1–16.

- Amalfitano, J. et al. 2022. Morphology and Paleobiology of the Late Cretaceous Large-Sized Shark Cretodus crassidens (Dixon, 1850) (Neoselachii; Lamniformes). Journal of Paleontology. 96 (5): 1166–1188.

- The earliest age at which a Genesis 5 patriarch is listed as having a son is 65, but it is difficult to imagine pre-Flood humans undergoing puberty around 13 years of age, like people today, and then routinely waiting 50 years to get married!

- von Bertalanffy, L. 1938. A Quantitative Theory of Organic Growth (Inquiries on Growth Laws II). Human Biology. 10 (2): 181–213.

- Natanson, L. J. and G. B. Skomal. 2014. Age and Growth of the White Shark, Carcharodon Carcharias, in the Western North Atlantic Ocean. Marine and Freshwater Research. 66 (5): 387–398.

- Nielsen, J. et al. 2016. Eye Lens Radiocarbon Reveals Centuries of Longevity in the Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus). Science. 353 (6300): 702–704.

- Hebert, J. 2024. Fossil Sharks Show Signs of Greater Past Longevity. Creation Science Update. Posted on ICR.org August 30, 2024, accessed March 25, 2025.

* Dr. Jake Hebert is a research associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in physics from the University of Texas at Dallas.