Evolutionary scientists view Earth’s rock layers as a chronological record of millions of years of successive sedimentary deposits. Creation scientists, on the other hand, see them as a record of the geological work accomplished during the great Flood’s year-long destruction of the Earth’s surface. If that is the case, though, why don’t we find dinosaur fossils in the earliest North American Flood sediment layers—why do we find them only in later Flood rocks? The ICR team’s recent examination of sedimentary rock layers across the United States and Canada seems to provide an answer.

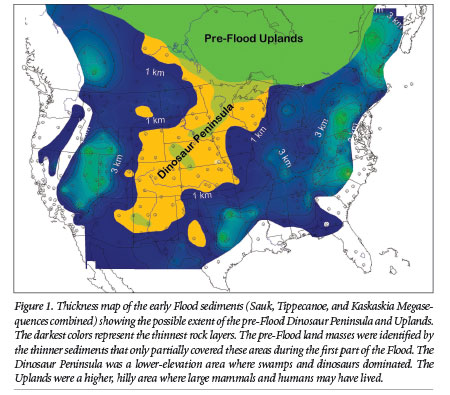

Deposition of the earliest Flood sediments (the Sauk, Tippecanoe, and Kaskaskia Megasequences) was thickest in the eastern half of the U.S.—often deeper than two miles! In contrast, the early Flood deposits across much of the West are commonly less than a few hundred yards deep, and in many places there was no deposition at all (Figure 1).

Deposition of the earliest Flood sediments (the Sauk, Tippecanoe, and Kaskaskia Megasequences) was thickest in the eastern half of the U.S.—often deeper than two miles! In contrast, the early Flood deposits across much of the West are commonly less than a few hundred yards deep, and in many places there was no deposition at all (Figure 1).

It seems the dinosaurs were able to survive through the early Flood in the West simply because they were able to congregate and scramble to the elevated remnants of land—places where the related sedimentary deposits aren’t as deep—as the floodwaters advanced. I call this high ground Dinosaur Peninsula. In this way, dinosaurs were able to escape burial in the early Flood.

However, later in the Flood (during deposition of the Absaroka and Zuni Megasequences) things changed dramatically. Pangaea, the former supercontinent made up of all of today’s continents, began to break up. This change in tectonics, combined with increasing water levels, caused great changes in the ways that the rock layers were deposited. Violent, tsunami-like waves washed across western North America while virtually no sedimentation was occurring in the East. This is a complete reversal of the pattern observed earlier in the Flood.

Rock sequence data show that more than three miles of sediment rapidly accumulated across the American West during the Absaroka and Zuni Megasequences.1 This apparently overwhelmed and buried the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous dinosaurs that couldn’t escape the Flood. As the waters rose, Dinosaur Peninsula began flooding from south to north. We also find the largest herds of dinosaurs, in the form of dinosaur fossil graveyards, in the Upper Cretaceous system sediments in northern Wyoming, Montana, and Alberta, Canada. It’s as if the dinosaurs were fleeing northward up the peninsula as the waters advanced from the south. By day 150 of the Flood (Genesis 7:24), even the Uplands area to the north, in present Canada, was covered by the floodwaters (Figure 1).

In his book Digging Dinosaurs, American paleontologist John R. (Jack) Horner reported the discovery of a huge dinosaur graveyard—over 10,000 adult Maiasaura in a small area, and yet no young were mixed in with them.2 What could have caused this odd sorting? In a Flood model, this is easily explained: The adult dinosaurs were likely stampeding away from the imminent danger of raging floodwaters; their young could not keep up and became engulfed in some lower part of the peninsula.

More research is being done on the stages of the Flood and the order in which the continents were submerged. But each answer provides new insight into the great catastrophe that forever altered the topography of our world.

References

- The data are taken from stratigraphic rock columns, outcrops, and holes bored deep in the earth to examine the different rock layers. To know the dimensions of megasequences, we have to look at many of these columns across a given area.

- Horner, J. R. and J. Gorman. 1988. Digging Dinosaurs. New York: Workman Publishing, 128.

* Dr. Clarey is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and received his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University.