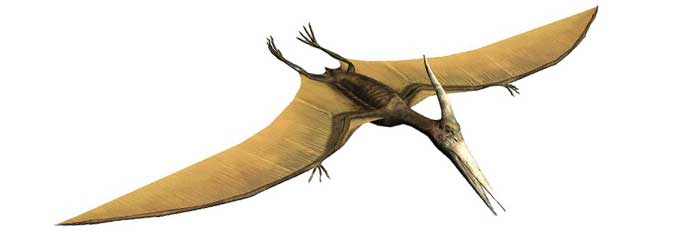

The great flying dragons of the sky, the pterosaurs, fascinate kids of all ages. With unique body adaptations such as an elongated fourth finger connected to wing membranes, this airborne hunter/scavenger was totally different from birds and other reptiles. An agile flyer with a "specialized brain and inner ear structure,"1 its fossil remains suddenly appear in the sediments, fully formed and with no evident ancestors.

In fact, there are two different suborders of flying reptiles: the long-tailed rhamphorhynchus type, and the short-tailed pterodactyls. Not only is there no clue as to which other reptile type gave rise to them, but the supposed relationship between them is obscure. As paleontologist Robert Carroll says, "No forms are known that are intermediate between rhamphorhyncoids and pterodactyloids."2 They appear fully functional and specialized for life in the air.

A standard paleontology textbook states, "The first pterosaurs from the late Triassic, such as Eudimorphodon from northern Italy, show all the unique characters of the group: the short body, the reduced and fused hip bones, the five long toes…, the long neck, the large head with pointed jaws and the arm. The hand has three short grasping fingers with deep claws and an elongated fourth finger that supports the wing membrane."3 From where did they acquire "all the unique characters of the group," so specialized and finely tuned?

Evolutionists maintain that the typical vertebrate forelimb exhibits homology (a similarity in biological form and function) with all other vertebrate forelimbs, and this is used as one of the classic "proofs" of evolution. This sounds reasonable, but it breaks down when the details of an unusual specimen, such as a pterosaur, are considered.

The pterosaur forelimb bears only scant resemblance to the normal vertebrate forelimb, if there is such a standard. The bones bear a rough correspondence to those of other creatures, but look at the differences! The finger placement and function are exceedingly different. The very long fourth finger to which the wing membrane is attached appears to be exquisitely designed to be the support for the wing tissue and nothing else. A transitional creature with an unusable long finger would have been a helpless mutant. Indeed, any transitional structure, not yet made useful by random mutation benefiting all related structures, would be detrimental, perhaps deadly.

What is meant by the claim that the pterosaur evolved from some other reptile? Do evolutionists propose that walking reptiles gradually acquired this marvelous form? Or do they claim it happened all at once, through a mega-mutation that affected numerous traits? Which came first--the excessively long finger, or the membrane connecting it to the body? When did the powerful flight muscles capable of utilizing this long finger arrive? Was it a separate event? The seeming irreducible complexity of the entire system argues for purposeful design.

On what evidence do scientists base their conclusion that pterosaurs evolved? How do we know it's true? As quoted above, the lowest (thought to be the earliest) time such a fossil appears in the record, it already has all its characteristic features. Sudden appearance in the fossil record is predicted by the creation model, and this is what we see.

Evolution further theorizes that certain reptilian dinosaurs evolved into flying birds, while other reptiles separately evolved into flying reptiles. The two types are not thought to be related, except through a hypothesized long-ago but unknown common ancestor. Yet each flying creature has so many precise features that enable it to thrive. Credibility is strained to think it could happen once, let alone twice--or more.

References

- Graham, S. "Smart" Wings Made Pterosaurs Agile Flyers. Scientific American, October 30, 2003.

- Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co., 336.

- Benton, M. J. 2005. Vertebrate Paleontology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 224.

* Dr. Morris is President of the Institute for Creation Research.

Cite this article: Morris, J. 2009. Flying Reptiles: A Lesson in Specialized Function. Acts & Facts. 38 (9):16.