My early memories of dinosaur teachings reflected the doctrine of their extinction 65 million years ago and the evolution of mankind only several million years ago. If that really happened, then our ancestors who lived before the scientific study of fossils should have had no knowledge of dinosaurs or similar creatures like pterosaurs and ichthyosaurs.

My early memories of dinosaur teachings reflected the doctrine of their extinction 65 million years ago and the evolution of mankind only several million years ago. If that really happened, then our ancestors who lived before the scientific study of fossils should have had no knowledge of dinosaurs or similar creatures like pterosaurs and ichthyosaurs.

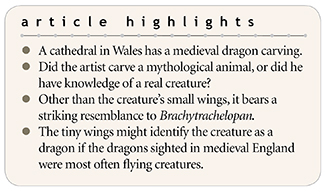

Certain pieces of ancient artwork appear to show just the opposite. I grabbed an opportunity to examine one such piece—a carved wooden dragon—found in St. Davids Cathedral in Wales. The ICR Discovery Center for Science & Earth History in Dallas displays a picture of this intriguing dragon art.

My wife and I visited the cathedral situated in picturesque Pembrokeshire, a far western headland of Wales. Religious buildings have occupied the site for a millennium. The current cathedral had its last big refurbishment in the 1800s, about 400 years after a major late-medieval upgrade, when the dragon-art piece was crafted. We ascended the slope-floored main area to several smaller chapels in the back.

One chapel featured folding seats called misericords. Each one is attached to a tall, straight-backed, dark, ornately carved wooden slot. They line three walls like a series of serene sentinels. Whereas medieval artists represented ecclesiastical themes with reverence, they brought a measure of whimsy to scenes, faces, and animals carved on the underside of each solid oak seat. When the seats are folded up, each carving is visible.

One misericord shows a dinosaur look-alike. Its overall anatomy resembles the sauropod dinosaurs known from fossils, with longer hind legs than front legs. These long-necked, extinct reptiles typify Jurassic rock layers. This one’s neck is not nearly as long in proportion to its main body as the more familiar sauropods like Diplodocus. Lest someone say its neck looks too short for the carving to represent any real sauropod, its neck length closely matches that of a dinosaur fossil found in Argentina in 2005 named Brachytrachelopan mesai.1

Two of the carving’s body details—small wings and ears—don’t match what fossils suggest.2 Like some modern cartoon dragons, these wings make no biological sense. The creature’s body would be far too massive for such tiny wings to support it in flight. Do these misfit features disqualify the piece from representing a real animal? It depends.

We first must ask if the unknown artist could have imagined by chance this particular animal form. The pure imagination hypothesis would explain the wacky wings, but it wouldn’t explain the long neck, long tail, legs positioned beneath a barrel-shaped body instead of straddle-legged like modern lizards, small head with sauropod-shaped mouth, and reptilian frills along its spine. When placed on a biology balance, the weight of creature features favors the idea that the artist somehow knew what sauropods looked like. If so, then he or she knew this centuries before scientists began to describe them from fossils.

This eyewitness hypothesis would benefit from an explanation of the ears and especially the wings. Until someone uncovers an ancient artist’s notebook that explains particular stylistic choices, we must reason it out. Medieval dragon depictions across Europe very often include wings. Perhaps artists placed wings on their large reptilian forms to identify them as dragons. In medieval Europe, the word dragon referred to reptiles. The St. Davids sauropod may represent a real, though extinct, reptile with imaginary body parts added on purpose. How could this happen?

If flying dragons were more widely known than fen-dwelling (wetland) dragons, then the artist could have added the flying serpent’s familiar wings to a lesser-known land dragon body just to make sure the viewer knew the creature was a reptile. Evidence that ancient inhabitants of the United Kingdom were familiar with flying dragons that we know today as pterosaurs would bolster this supposition. One sober 18th-century Scottish account reads:

In the end of November and beginning of December last, many of the country people observed…dragons…appearing in the north and flying rapidly towards the east, from which they concluded, and their conjectures were right, that…boisterous weather would follow.3

And according to an approximately 19th-century Welsh anecdote, “the woods around Penllyne Castle, Glamorgan, had the reputation of being frequented by winged serpents, and these were the terror of old and young alike.”4 If flying dragons hadn’t yet been eradicated from the UK by the 1700s, then the animals must have been around to terrorize old and young long before then—for example, in medieval times when the St. Davids carvers lived.

Whoever would reject the wings-equal-dragon hypothesis still needs to explain the wealth of short-necked sauropod-specific anatomy on the St. Davids misericord. The larger weight of evidence lies on the side of artists who had some measure of eyewitness knowledge of their subject matter. This remarkable art forces a rethink of secular dinosaur doctrines but happens to fit perfectly with a biblical view of dinosaurs.5

References

- Creation researcher Vance Nelson connected the carving to this fossil in his book Dire Dragons. Nelson, V. 2012. Dire Dragons. Red Deer, Canada: Untold Secrets of Planet Earth Publishing Co.

- A third detail—webbed feet—could have represented a wetland habitat.

- Flying Dragons at Aberdeen. 1793. A Statistical Account of Scotland. 6: 467. Quoted in Cooper, B. 1995. After the Flood. Chichester, UK: New Wine Press, 141.

- Trevelyan, M. 1973. Folk-Lore and Folk-Stories of Wales. Yorkshire, UK: EP Publishing Limited, 169. The passage adds on page 170: “An aged inhabitant of Penllyne, who died a few years ago, said that in his boyhood the winged serpents were described as very beautiful….This old man attributed the extinction of winged serpents to the fact that they were ‘terrors in the farmyards and coverts.’”

- God created dinosaurs when He “made the beast of the earth according to its kind” (Genesis 1:25). Noah’s Flood fossilized many of them, when “all flesh died that moved on the earth: birds and cattle and beasts and every creeping thing that creeps on the earth” (Genesis 7:21). Some dinosaurs presumably survived the Flood on board Noah’s Ark, where “they went into the ark to Noah, two by two, of all flesh in which is the breath of life” (Genesis 7:15). Centuries later, God told Job, “Look now at the behemoth….He moves his tail like a cedar,” probably indicating a sauropod living near where “the Jordan [River] gushes” (Job 40:15-23). These and many other historical records challenge evolutionary beliefs about dinosaur extinction.

* Dr. Thomas is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in paleobiochemistry from the University of Liverpool.