Many evolutionists fail to see what is “hidden in plain view” for the same reason British Celts saw the wrong thing when Julius Caesar attacked them in 54 BC. Since the Britons never recruited multi-ethnic mercenaries, instead of seeing one invading force, they reported Caesar’s beach landing as an attack by combined armies of Rome, Libya, and Syria.1 They saw what their presuppositions led them to see. Likewise, evolutionists misinterpret many facts in plain view due to their erroneous assumptions.

Many evolutionists fail to see what is “hidden in plain view” for the same reason British Celts saw the wrong thing when Julius Caesar attacked them in 54 BC. Since the Britons never recruited multi-ethnic mercenaries, instead of seeing one invading force, they reported Caesar’s beach landing as an attack by combined armies of Rome, Libya, and Syria.1 They saw what their presuppositions led them to see. Likewise, evolutionists misinterpret many facts in plain view due to their erroneous assumptions.

Last month’s article examined the evolutionary concept of ecosystem engineering, which considers the proactive way in which animals alter their environments.2 Although this is an improvement on the evolutionary view that organisms are passive recipients rather than active participants, it still misses the best lessons these animals teach. Two examples of such misunderstanding are considered below.

“Bigger Is Better”

Some ecologists try to limit the application of the ecosystem engineering concept to the impactful and “big” habitat alterations made by animals. Thus, beaver dams and coral reefs are “big enough” to qualify as ecosystem engineering habitat modifications, but bird nests and prairie burrows are often dismissed as de minimis—not worthy of comparable attention.2

This is a “bigger is better” fallacy, which is a manifestation of an anthropocentric (human-centered) viewpoint that evaluates a situation only from the human perspective. If something doesn’t seem big to us, it must not be significant. But ecologically speaking, which is more important: a huge elephant or a microscopic yet deadly virus? Which can ultimately have the bigger impact?

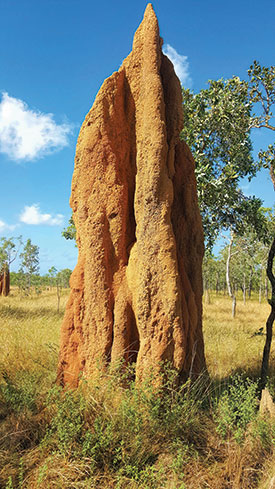

An anthropocentric perspective is unrealistic when evaluating whether animal activity is “big enough” to be ecologically important. For example, consider how deadwood-eating termites aggressively modify their neighborhoods. They use saliva-soil mud to build air-conditioned mud “chimneys” above interconnected underground tunnels. Mounds built by Australia’s Amitermes meridionalis termites can be 12′ tall, 8′ wide, and 3′ deep.3

An anthropocentric perspective is unrealistic when evaluating whether animal activity is “big enough” to be ecologically important. For example, consider how deadwood-eating termites aggressively modify their neighborhoods. They use saliva-soil mud to build air-conditioned mud “chimneys” above interconnected underground tunnels. Mounds built by Australia’s Amitermes meridionalis termites can be 12′ tall, 8′ wide, and 3′ deep.3

Consider that Amitermes worker termites are about a third of an inch long. The termites-to-mound height ratio is thus 432:1. This is comparable to humans constructing spit-mud mounds 2,592′ high—in relative terms, almost double the height of the Empire State Building. To a human, the mound chimney might be just a big mud pile, but to a worker termite it’s an enormous skyscraper!

Another example is found in Chesapeake Bay, which is burdened with excess nitrogen and organic nutrients that people release into its tributaries. The nitrogen compounds fuel picoplankton, which comprise ~15% of bay phytoplankton biomass during the summer. If left unchecked, their growth would lead to algal blooms that would block sunlight from submergent aquatic plants, leading to oxygen-depleted “dead zones.”4

Thankfully, oyster reefs, bolstered by attached mussels, filter huge volumes of the bay’s water and consume the otherwise unrestrained picoplankton. This filtering ultimately benefits the dissolved oxygen and accessible underwater sunlight needs of the interactive Chesapeake Bay ecosystem.4

Humans might discount the teeming gazillions of picoplankton simply because they’re too small for us to see, but we shouldn’t discount the importance of the bivalves’ impact in keeping their environmental waters clear enough of picoplankton to sustain life. The combined filtering of eastern oysters and hooked mussels provides estuarial water clean-up services “hidden in plain sight.”

God designed and purposefully engineered both big and small creatures to play important roles in Earth’s ecology. ![]()

Who Engineered These Small-Yet-Great Ecosystem Benefits?

Like the ancient Britons, ecologists who embrace ecosystem engineering can miss what’s happening because they see what their presuppositions lead them to expect. But even more, they can miss the significance of what they see. Creatures proactively engage with and change their environments, but they don’t “engineer” anything. That glory goes to creation’s Architect and Bioengineer, the Lord Jesus Christ, who designed, built, and maintains all of these small-yet-great super-interactive ecosystems (Revelation 4:11).

References

- Cooper, B. 1995. After the Flood. Chichester, UK: New Wine Press, 58-59.

- Ecosystem engineering analysis improves upon earlier “keystone species” concepts yet ultimately fails to identify the true cause and logic underlying animal successes in filling various habitats. Johnson, J. J. S. 2019. Ecosystem Engineering Explanations Miss the Mark. Acts & Facts. 48 (3): 20-21, illustrating 2 Timothy 3:7.

- Grigg, G. C. 1973. Some Consequences of the Shape and Orientation of ‘Magnetic’ Termite Mounds. Australian Journal of Zoology. 21 (2): 231-237. (Amitermes meridionalis termite mounds are sometimes four meters high.)

- Gedan, K. B., L. Kellogg, and D. L. Breitburg, 2014. Accounting for Multiple Foundation Species in Oyster Reef Restoration Benefits. Restoration Ecology. 22 (4): 517-524. See also Pipkin, W. 2018. Freshwater bivalves flexing their muscles as water filterers. Chesapeake Bay Journal. 28 (7): 1.

* Dr. Johnson is Associate Professor of Apologetics and Chief Academic Officer at the Institute for Creation Research.