Yellowstone became the world’s first national park in 1872. Geologist Ferdinand Hayden led an expedition the year before through much of what became the 2.2 million-acre park, and his report helped convince the U.S. Congress to set aside the land for that purpose. It occupies the northwestern corner of Wyoming and spills into Idaho and Montana.

Yellowstone became the world’s first national park in 1872. Geologist Ferdinand Hayden led an expedition the year before through much of what became the 2.2 million-acre park, and his report helped convince the U.S. Congress to set aside the land for that purpose. It occupies the northwestern corner of Wyoming and spills into Idaho and Montana.

The park is unique for its travertine flows, mud pots, hot springs, and canyons. It houses over 10,000 thermal features and over half the world’s geysers.1 Its otherworldly landscapes plus raw wildlife have been sufficient causes to protect the region for generations. In this two-part series, we’ll explore park features that fit well with biblical history.

Volcanic Beginnings

Yellowstone is one of about 12 supervolcanoes in the world. Thick layers of volcanic ejecta from huge eruptions cover most of the area and beyond. The middle of the park is a volcanic plateau that lies about 7,300 feet above sea level. Yellowstone Lake rests within the plateau, and mountain peaks taller than 11,000 feet surround it.

The central plateau has three overlapping calderas, or collapsed volcanoes. Each collapse occurred after a major eruption. The largest eruption occurred first, and the smallest happened last. This trend reveals diminishing power over time instead of the steady processes that uniformitarians imagine. That scenario fits what we would expect as Earth recovered from the tumultuous Flood about 4,500 years ago.2

Geologists noticed a line of older calderas that extends from Yellowstone to Oregon. Conventional scientists consider this trail to have formed from a mantle hot spot as Earth’s crust slowly moved across it over millions of years.3

However, millions-of-years age assignments rely on an assumed evolutionary timeline, not directly on data. The Institute for Creation Research has a far better interpretation. Evidence continues to build that Earth’s tectonic plates moved much faster during the Flood year.4 Rapid relative movement of North America over a mantle hot spot likely formed the volcanic trail, perhaps within months. Catastrophic conditions slowed dramatically after the Flood. Today, we see little plate motion or volcanism at Yellowstone.

The magma source at Yellowstone is high in silica (quartz-rich). This resulted in especially violent eruptions. In contrast, basalt magmas are lower in silica and flow more gently, like those erupting in Hawaii. Silica-rich continental crust likely altered the deep mantle magmas that rose to the surface at Yellowstone. This unique magma chemistry also helps explain its geysers and hot springs.

Geysers and Hot Springs

Geysers are hot springs that emit jets of hot water and steam. They need an active shallow heat source to superheat groundwater into steam. Yellowstone provides that with magma detected just three miles below the surface.5

They also need a fairly watertight plumbing system.6 The silica-rich magma provides that too. Silica dissolves in circulating hot groundwater. It then drops out of solution (precipitates) onto the fracture surfaces and conduits to form a hard deposit called sinter. This deposit seals water in and makes constrictions that allow geysers to build up pressure.6

Water underground expands as it warms until spaces inside the conduits become compressed, like a pressure cooker. Steam and fluids rise, and in places reach Earth’s surface at nearly 200°F, sometimes jetting into the sky.6 Creation scientists speculate how the geysers might illustrate the eruptions through great fractures that took place around the planet when the fountains of the great deep burst open at the start of the Flood (Genesis 7:11).

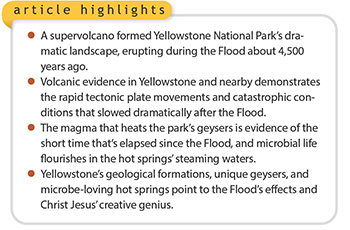

Old Faithful

Yellowstone’s most popular geyser, Old Faithful, may not produce the tallest eruption—although its 130 feet-plus average is impressive—but, as its name implies, it’s one of the most predictable. This regularity stems from its steady source of underground water.

But Old Faithful does change. Several decades ago, it averaged less time between eruptions. Local tremors have since lengthened that time.7 Geysers like Old Faithful point to the role that water played in the formation of Earth and then its reformation during the Flood (2 Peter 3:5-6).

Rainbow Pools

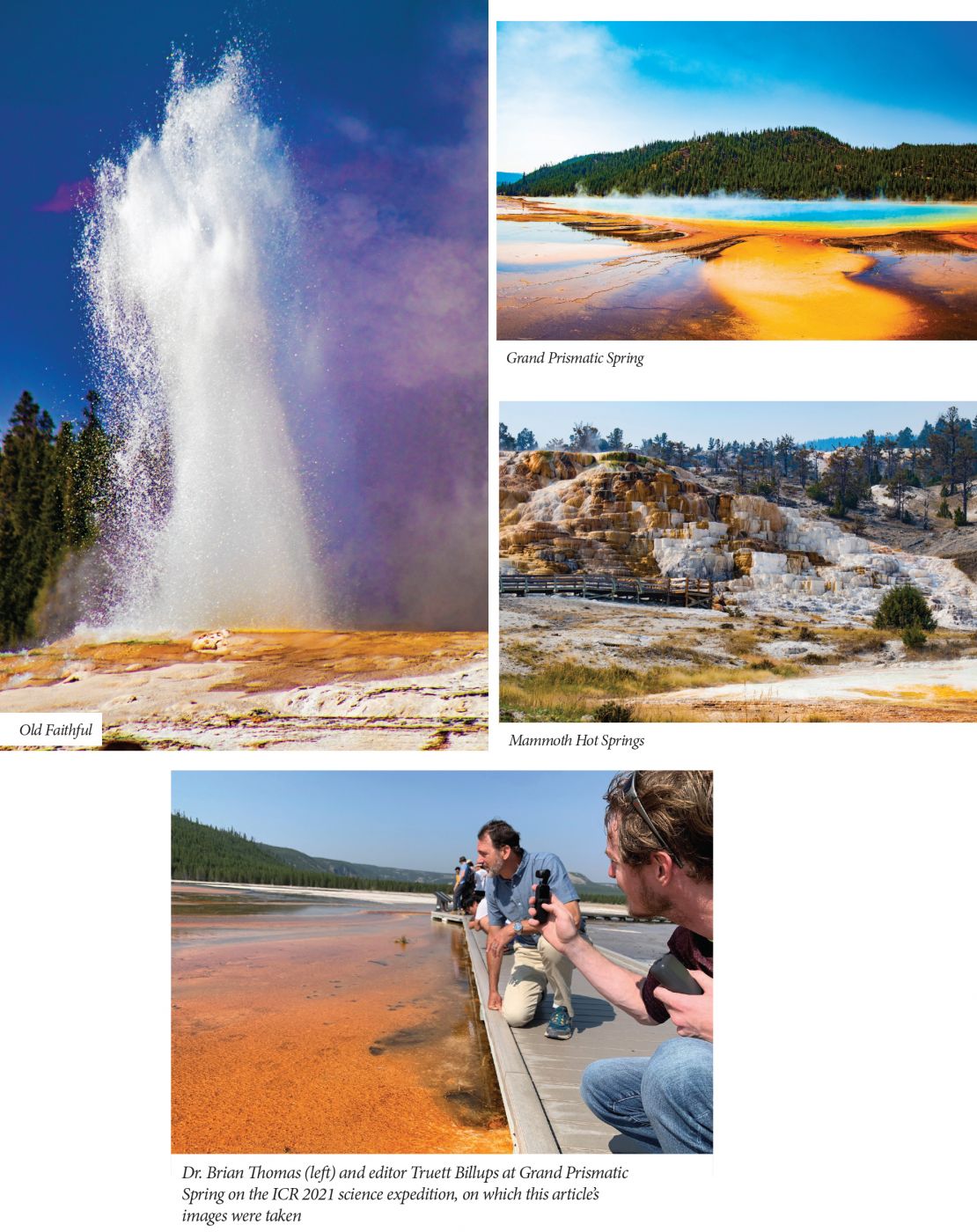

Rainbow-colored hot springs like Grand Prismatic Spring may present the most striking of Yellowstone’s natural wonders. Different microbial mats form rainbow-like rings when viewed from above. Ferdinand Hayden stated in 1871, “Nothing ever conceived by human art could equal the peculiar vividness and delicacy of color of these remarkable prismatic springs.”8

Hot water rising from depth cools as it flows from the center of the pools. Heat-loving (thermophilic) microbes called Synechoccus use unique biochemistry to pioneer the perimeter of the 370 foot-diameter Grand Prismatic Spring. They live there at about 150°F (65.6°C).9

These cyanobacteria harvest sunlight to obtain energy. In the summer, they deploy yellow pigments to protect their vital DNA from the sun’s UV rays. Remarkably, they use those same pigments to reassign that would-be-damaging light energy toward their green pigments (chlorophylls) for photosynthesis.

Outside the pool’s yellow ring grows a mixture of microbes that together look orange. An even wider red ring lies outside of that. The wider variety of microbes here also use their pigments for protection and light harvesting, but each variation harvests a different part of the light spectrum available for photosynthesis. As the microbes share the light, they convert and store its energy into sugars.

These marvelous microbes form strings, filaments, and mats as they trade resources. Surface dwellers give their sugars to microbes beneath them and receive other nutrients in return. None of this works without precision microengineering, for which an actual engineer like the Lord Jesus deserves full credit.

Mammoth Hot Springs

Hot springs can bring up dissolved lime, sulfur, and even mud. North of Yellowstone’s main caldera, Mammoth Hot Springs conveys two tons of dissolved lime from depth per day.5

The water here likely gets its heat not from magma like the geysers but from Earth’s thermal gradient (increasing temperature with depth) far beneath the surface. The complex at Mammoth Hot Springs covers nearly a square mile and deposits more lime than any other spring in the world.6

As the water cools at the surface, lime precipitates to form travertine, a form of limestone, in a complex of terraces. Travertine deposits can grow fast under the right conditions. Extrapolating today’s deposition rate into the past shows that this hot spring complex has been active for only thousands of years.

Conclusion

Yellowstone is a beautiful and awe-inspiring reminder of the global Flood. Calderas and thousands of feet of volcanic rock bear witness to great catastrophes that occurred during the Flood year. The magma that powers active geysers has not yet fully cooled, which is what would be expected from the relatively short time since the Flood.

Christ Jesus’ creative genius explains the microbes that collaborate to thrive in extremely hot waters. The hot springs display part of the Lord’s provision of the hydrologic cycle that moves water around our planet. Although the Flood destroyed the world that then was, it left behind beauty and wonders that point us to Him.

References

- Tweit, S. J. 1999. Yellowstone. In America’s Spectacular National Parks. L. B. O’Connor and D. Levy, eds. Los Angeles, CA: Perpetua Press, 76-79.

- Austin, S. A. 1998. The Declining Power of Post-Flood Volcanoes. Acts & Facts. 27 (8).

- A hot spot is thought to form from a near-stationary deep mantle plume of high heat capable of producing a melt through the overriding crust.

- Clarey, T. Plate Subduction Beneath China Verifies Rapid Subduction. Creation Science Update. Posted on ICR.org December 23, 2020, accessed February 12, 2022; Clarey, T. 2020. Carved in Stone: Geological Evidence of the Worldwide Flood. Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research.

- How big is the magma chamber under Yellowstone? U.S. Geological Survey FAQ. Posted on usgs.gov, accessed February 17, 2022.

- Hacker, D. and D. Foster. 2018. Yellowstone National Park: Northwest Wyoming, Eastern Idaho, Southern Montana. In The Geology of National Parks, 7th ed. D. Hacker, D. Foster, and A. G. Harris, eds. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt, 765-791.

- Milstein, M. Old Faithful slows, but grows. Billings Gazette. First captured online January 17, 2001. Retrieved from web.archive.org January 11, 2022.

- Theurer, J. Colors of Curiosity: Yellowstone’s Microbes. Yellowstone Quarterly. Posted on yellowstone.org April 16, 2019, accessed January 13, 2022.

- Geiling, N. The Science Behind Yellowstone’s Rainbow Hot Spring. Smithsonian Magazine. Posted on smithsonianmag.com May 7, 2014, updated May 12, 2016, accessed January 14, 2022.

* Drs. Clarey and Thomas are Research Scientists at the Institute for Creation Research. Dr. Clarey earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University, and Dr. Thomas earned his Ph.D. in paleobiochemistry from the University of Liverpool.