by Tim Clarey, Ph.D., and Mike Mueller, M.S.*

Nestled next to Medora, North Dakota, and 45 miles east of Glendive, Montana, Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) consists of three separate units. The North and South Units are 68 miles apart with the Elkhorn Ranch Unit in between. All total, the park encompasses 70,446 acres.1 It was established in 1947 as a national memorial to President Roosevelt for people to experience his beloved North Dakota badlands and early ranching days.

Theodore Roosevelt first came to the Dakota Territory in 1883 to hunt bison. A year later, after his mother and first wife had both died, he returned as a cattle rancher and established the Maltese Cross and Elkhorn Ranches.1 Although the ranches ultimately failed, he credited his time in the Dakotas as the basis for his becoming America’s “conservationist” president.

In 1906, he signed the Antiquities Act, establishing 18 national monuments with Devils Tower as the first. He was also instrumental in creating five national parks and 150 national forests, ultimately protecting over 230 million acres of federal land.1 In 1918, he said, “I never would have been President if it had not been for my experiences in North Dakota.”1

Formed by the Global Flood

TRNP consists of a vast badlands landscape of flat-topped hills and isolated buttes. The sedimentary rocks in the park are members of the late-Flood (Cenozoic) Fort Union Group and contain mudstone, volcanic ash, sandstone, and lignite (low-grade coal).2 Conventional geologists claim these rocks were deposited by a series of rivers, swamps, and lakes long after the dinosaurs went extinct.

But this interpretation doesn’t explain what visitors see at the park. Instead, four observations testify that the receding waters of the global Flood were instrumental in the creation of the rocks and the landscape at TRNP.

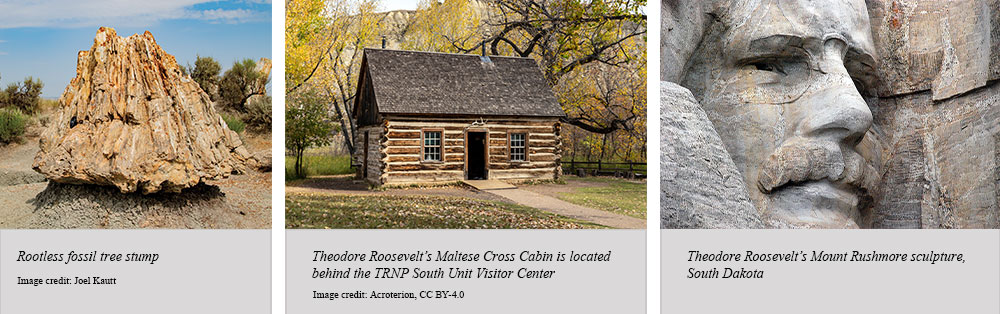

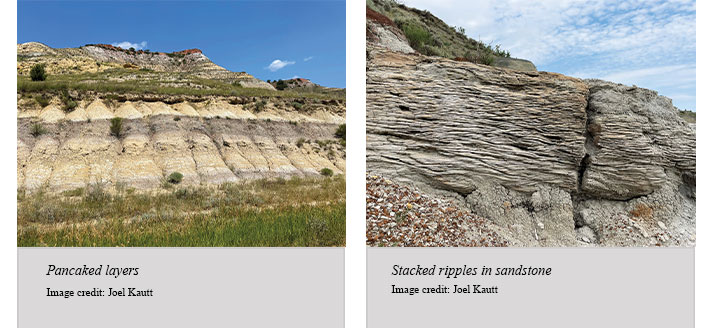

1. Extensive Pancaked Bedding

The stacked sediments in the park are beautifully colored individual beds that extend as far as the eye can see. What river system today spreads thin layers of sediment, many a few feet thick or less, over such vast areas, stacking them like pancakes? Rivers carve channels, but we don’t see many channels cut into these layers.

Only broad and extensive flows of water can spread the thin layers we observe in TRNP. Plus, many of the beds contain ripples, cross-beds, and evidence of soft-sediment folding and slumping.2 All of these features tell us the sediments were deposited quickly by fast-moving water. A better interpretation is that these rocks were laid down during the receding phase of the Genesis Flood.3

2. Planation Surfaces and Badlands

TRNP is surrounded by the fairly featureless Dakota Prairie Grassland. There are also many flat horizons within TRNP called planation surfaces. These surfaces are interrupted by isolated buttes and flat tops. The park’s interpretive signs describe the Little Missouri River and its tributaries eroding the soft sedimentary layers of the northern Great Plains over thousands of years. And they claim that the river, wind, ice, and plants continue their erosive action today.4

But the Little Missouri River is too small and carries much too little sediment to create the present topography. In addition, the eroded material has been completely removed from the region, leaving the featureless grasslands around the park. A lot of water flow is needed to plane off the tops of hills and wash the sediment completely away. The receding water of the Flood 4,500 years ago is a better choice to have constructed the landscape at TRNP.

3. Flat Coal Beds Proclaim the Flood

Along the South Unit’s scenic loop trail are sites like Coal Vein Trail and Scoria Point Overlook. These reflect the many thin lignite (coal) beds within the sedimentary deposits of the park. Scoria, sometimes called clinker, is a term used for rocks altered by the heat emitted when adjacent coal layers get cooked underground. Many lignite beds were ignited by lightning strikes. Scoria is often dark red or black and is bubbly-looking.

The conventional interpretation says the coal in TRNP was deposited millions of years ago when this area was a swamp. But the near perfectly flat tops and bottoms of the coal beds tell a different account that supports the biblical Flood. Real swamps, where plants grow in place, show roots protruding downward, disrupting the bottom of the layers. Instead, these flat-bottomed lignite beds were caused by the transportation of massive vegetation mats torn loose from pre-Flood lands by the Flood. They were immediately buried and compressed by mudflows, volcanic ash, and sand slurries into the flat layers we observe.

4. Petrified Forest, a Biblical View

The Petrified Forest Trailhead sign tells visitors that

Sixty million years ago, this land looked similar to today’s Florida Everglades. Abundant water and a warmer climate promoted the growth of large trees. Giant petrified stumps and logs are remnants of this ancient wetland.

As with most park interpretations, the sign gets some things right, but the Genesis Flood is a better explanation. Trees that are very similar to today’s bald cypress, magnolia, and sequoia are found as rootless stumps and branchless logs all along the trail. Many are in a near-upright position.2 But the trees were clearly transported by water, like the material that makes up the lignite beds was. They did not grow in these positions or they would still have their roots embedded in the layers below.

Instead, these trees were torn loose from where they grew, transported by floodwaters, and deposited rapidly. Gravity pulled the heavier ends down when they settled. These tree remnants were likely carried by massive sediment flows draining off the pre-Flood uplands to the north.3 Dissolved silica in groundwater from the volcanic ash layers led to their fossilization, replacing the original tissues and making petrified wood.5

Conclusion

Theodore Roosevelt National Park showcases layers of exposed sedimentary rock, fossil trees, and other features that are wellexplained by the Flood of Noah that occurred about 4,500 years ago. This global cataclysmic event accounts for the deposition of the thin and extensive layers, lignite beds, and tree stumps within the park. And the flat-topped buttes, the fairly featureless grasslands, and the rugged badlands topography reflect the erosive power of the receding floodwaters. Even energy resources, like the coal beds at TRNP and elsewhere, are leftovers from this horrible judgment.

Although God destroyed the pre-Flood world, He preserved life on the Ark and provided all of the resources necessary for humanity to flourish after the Flood. And He set His rainbow in the clouds as a sign of His covenant to never again destroy the world with water (Genesis 9:12–16).

References

- National Park Service. Exploring Theodore Roosevelt National Park. U.S. Department of the Interior. Government Printing Office: 2023–423-201/83068. Last updated 2023.

- Biek, R. F. and M. A. Gonzalez. 2001. The Geology of Theodore Roosevelt National Park: Billings and McKenzie Counties, North Dakota. Miscellaneous Series, no. 86. Bismarck, ND: North Dakota Geological Survey.

- Clarey, T. 2020. Carved in Stone: Geological Evidence of the Worldwide Flood. Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research.

- Theodore Roosevelt National Park Visitor Center Interpretive Displays. 2024. Medora, ND.

- We discussed this process in Thomas, B. and T. Clarey. 2021. The Painted Desert: Fossils in Flooded Mud Flats. Acts & Facts. 50 (4): 16–19.

Dr. Clarey is director of research at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University. Mr. Mueller is president of the Institute for Biblical Authority and earned his B.S. and M.S. in biology education and natural resource/wildlife management from Pittsburgh State University.