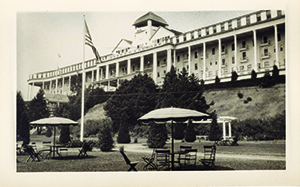

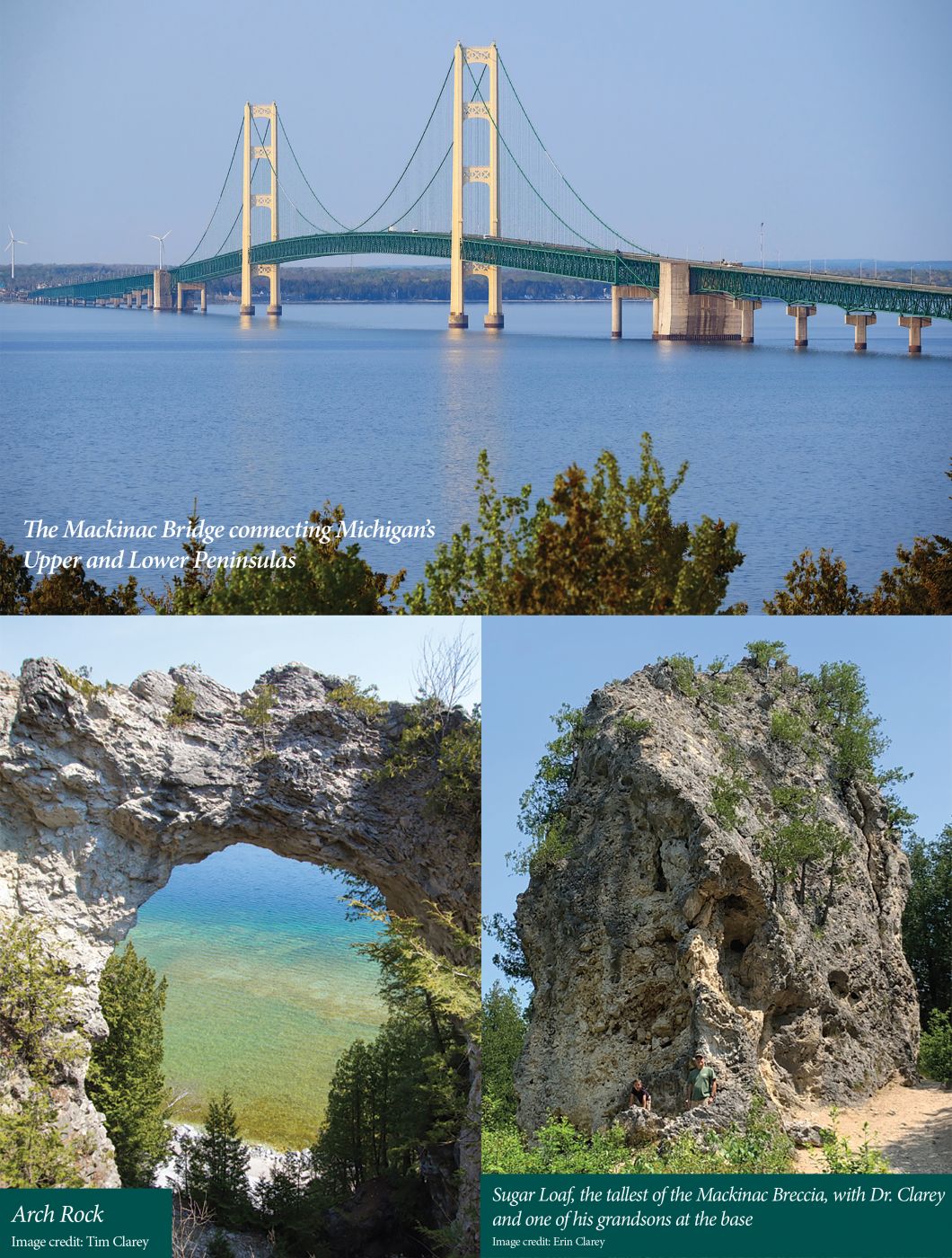

Originally designated in 1875 as America’s second national park, Mackinac Island’s federal land was transferred to the State of Michigan in 1895 and became its first state park.1 It remains one of the top tourist destinations in the state. Pronounced “mak-in-aw,” the 3.8-square-mile island is nestled between Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsulas on the Lake Huron side of the nearly five-mile-long Mackinac Bridge. Known for its lack of automobiles, the island boasts a Revolutionary War-era fort and the Grand Hotel, with a 660-foot porch.

But the story of the island goes back to the global Flood, with rocks exposing sediments from the earliest weeks of that cataclysm. Post-Flood wave-cut cliffs preserve a history of fluctuating lake levels during the Ice Age. And an accident on the island involving a bullet wound that didn’t fully heal revealed God’s design in the human digestive system.

Flood Beginnings and Collapses

Mackinac Island exposes rocks from two of the earliest megasequences of the Flood, the Tippecanoe and the Kaskaskia. The Kaskaskia is the younger of the two and lies on top of the Tippecanoe. Globally, these layers are filled with shallow-water marine fossils, since at that point the floodwaters had not yet begun to cover the dry land.2

Some of these rocks are visible near the center of the island on the highest point. Referred to as the Ancient Island, its peak is about 275 feet above today’s Lake Huron.1 Here, near the War of 1812-era Fort Holmes, some of the lower Kaskaskia sediments are exposed, known as the Devonian Bois Blanc Formation. Below this half-mile-long hill and across most of the island reside carbonate rocks of the upper Tippecanoe Megasequence (Silurian St. Ignace Dolomite). These two sedimentary layers make up the bulk of the island and were most likely deposited within the first 40 days of the Flood.2 They were exposed as the floodwaters receded and were further sculpted by the post-Flood Ice Age.

Scattered around the island are several prominent “sea” stacks composed of broken and angular pieces of rock. These resistant spires, stacks, arches, and even a cave are composed of Mackinac Breccia. Breccia is made up of broken, angular chunks of rock melded together. The largest stack of Mackinac Breccia is called Sugar Loaf and is about 75 feet tall. Arch Rock is a rare formation of limestone breccia and stands on the Lake Huron shoreline 146 feet above the water.

These stacks formed in a manner similar to a sinkhole and were the product of salt dissolution and collapse. In this case, the sediments composing the broken pieces were deposited on top of the St. Ignace Dolomite. Below this dolomite lie earlier Flood rocks that are rich in salt.

During the Flood’s continued advance, water was forced into the ground and dissolved some of the salt. With no support from below, the overlying sediments collapsed, dropping fragments from above into the vacant cavity. Swirling groundwater cemented these broken fragments together, and, rather oddly, they became more resistant than the surrounding bedrock.

As the receding Flood stripped away the surface layers, the breccia stacks were left behind as “sea” spires. Glacial lake water further carved some of these into caves such as Skull Cave and arches such as the previously mentioned Arch Rock.

Rapidly Carved Ice Age Cliffs

Native Americans referred to the island as Michilimackinac, or “place of the great turtle,” because in profile the island resembles a turtle’s back.3 This appearance is due to erosion during the two primary Ice Age lake levels, the older Lake Algonquin and the younger Lake Nipissing. The Ancient Island was all that was exposed above the water line when Lake Algonquin crested at over 230 feet above the present lake level. Its waves carved a steep cliff marking the edge.

As the lake levels further dropped, over two dozen successive shoreline ridges were formed prior to the formation of Lake Nipissing. This younger level was only about 50 feet above the level of Lake Huron today. It also formed a 45- to 50-foot wave-cut cliff that nearly circles the island. Fort Mackinac was established on this cliff in 1780, as was the Grand Hotel in 1887.3

The two prominent wave-cut cliffs and the numerous shoreline ridges preserve evidence of the many changing Ice Age lake levels. These features always seem to be present wherever Ice Age lakes resided. In fact, similar wave-cut terraces are found surrounding the Great Salt Lake in Utah (ancient Lake Bonneville) and around the glacial Lake Missoula in western Montana.

Wave-cut cliffs don’t take thousands or even hundreds of years to develop. In fact, these landforms can occur in just a few weeks.4 Creation scientists calculate that the Ice Age lasted about 500 to 700 years after the Flood.5 The development of these landforms easily fits within the biblical timeline.

Design in Human Digestion Revealed

Mackinac Island is also famous for a digestive-related reason. And it’s not the island’s delicious fudge that’s made each summer to fuel hungry tourists. Rather, it’s because an accident on the island led to some of the earliest studies of human digestion.

It began with a blast in 1822 in the American Fur Company store on the island’s Main Street. A gun accidentally discharged into the abdomen of Alexis St. Martin, a young French Canadian. Fort Mackinac’s post surgeon, Dr. William Beaumont, was called. After St. Martin was patched up, he was left with a hole, or fistula, in his stomach that didn’t fully heal. In 1825, Dr. Beaumont decided to do some experiments on his young patient, since at the time no one knew much about the digestive process.

Beaumont commenced his experiments in May at Fort Mackinac. As St. Martin lay on his right side, the doctor peered into his stomach and observed the stomach’s reaction to food and drink. He siphoned out fluids and retrieved food with a spoon to see how it had changed since entry. Frequently he suspended pieces of raw or roasted meat on string to find out how long digestion took. Once he substituted a plug of beef for cloth over the orifice; five hours later, he noted it had been “completely digested off, as smooth and even as if it had been cut with a knife.” 6

Dr. Beaumont conducted a total of 250 experiments on St. Martin that first year. He eventually published the results of his groundbreaking discoveries in a book on human digestion.7 A horrible accident on a remote island and an inquisitive army doctor who had a lifelong faith in God together unlocked some of the mysteries of our wonderfully designed human body.

Mackinac Island State Park thus showcases the Flood, the Ice Age, and the engineering prowess of our Creator, the Lord Jesus Christ.

References

- Milstein, R. L. 1987. Mackinac Island State Park, Michigan. In North-Central Section of the Geological Society of America: Centennial Field Guide, vol. 3. D. L. Biggs, ed. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America, 285-288.

- Clarey, T. 2020. Carved in Stone: Geological Evidence of the Worldwide Flood. Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research.

- Porter, P. 2013. Historic Mackinac Island Visitor’s Guide: Tours, History, Maps. Mackinac Island, MI: Mackinac Island State Park Commission.

- Clarey, T. 2020. Lava Flows Disqualify Lake Spillover Canyon Theory. Acts & Facts. 49 (10): 10-12.

- Oard, M. J. 2004. Frozen in Time: The Woolly Mammoth, The Ice Age, and the Bible. Green Forest, AR: Master Books.

- Widder K. R. 2006. Dr. William Beaumont: The Mackinac Years. Mackinac Island, MI: Mackinac Island State Park Commission.

- Beaumont, W. 1838. Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion. Edinburgh: MacLachlan and Stewart.

* Dr. Clarey is Research Scientist at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University.