Researchers over the past decade have been characterizing new, previously hidden genetic codes embedded within the same sections of genes that code for proteins—utterly defying all naturalistic explanations for their existence. This same linear sequence of genetic information that encodes multiple programming languages with different instructions is truly evidence of supernatural engineering that can only be ascribed to the all-powerful and all-wise Creator.

Researchers over the past decade have been characterizing new, previously hidden genetic codes embedded within the same sections of genes that code for proteins—utterly defying all naturalistic explanations for their existence. This same linear sequence of genetic information that encodes multiple programming languages with different instructions is truly evidence of supernatural engineering that can only be ascribed to the all-powerful and all-wise Creator.

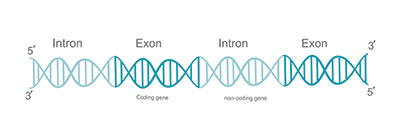

In addition to supplying many different types of genetic code that regulate function, the genome also provides highly complex coded templates for making a wide diversity of functional RNA molecules and proteins. Protein-coding genes contain key information to make proteins and contain the most studied type of genetic code. Some of the most important chunks of code in protein-coding genes, called exons, are those segments that specify the actual template for protein sequences.

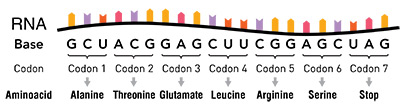

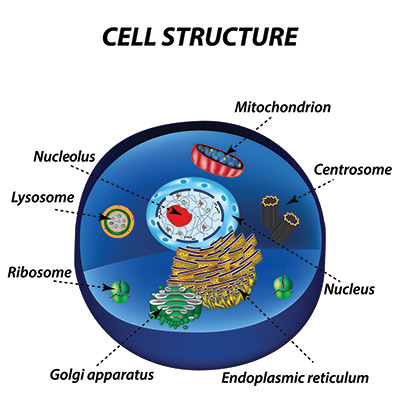

In exons, three consecutive DNA letters form what is called a codon, and each codon corresponds to a specific amino acid in a protein. Long sets of codons in genes contain the protein-making information that ends up being represented in an RNA copy of the gene used to translate (create) entire proteins, which may be hundreds of amino acids in length, using cellular machinery (ribosomes).

In the early days of molecular biology, when the genetic code was being deciphered, codons initially appeared to possess some redundancy. This was because there are 61 codons in contrast to only 20 amino acids. As far as specifying a particular amino acid, the first two bases in the codon structure are the same, but the third base can vary.

For example, the codons GGU, GGC, GGA, and GGG all encode the same amino acid called glycine. When scientists first discovered this phenomenon, they called the variation in the third base a “wobble” and, out of ignorance, simply relegated the variability as redundant or degenerate. In other words, they assumed that all the different codon variants for a given amino acid were functionally equivalent.

Until recently, scientists believed that the protein-coding regions of genes had mysterious signals other than codons that told the cell machinery how to regulate and process the RNA transcripts (copies of genes) prior to making the protein. Researchers originally thought that these regulatory codes and the protein template codes containing the codons operated independently of each other, but they no longer think this. These codes are embedded in the “wobble” base.

The Discovery of Duons

Transcription factors are specialized protein machinery that bind in and around genes at specific sites called regulatory regions to turn them on and regulate how fast they run and how much product they produce. In transcription, messenger RNAs (mRNAs) are produced from genes—some of which are used to make templates for proteins, while others are used to make functional or structural RNAs (called long non-coding RNAs).

In 2013, a study was published in which researchers mapped the locations of where transcription factors were binding in active genes.1 They were surprised to discover that a significant proportion of the binding sites contained codons and that the third base in a codon contained information for the binding of a specific type of transcription factor in addition to coding for an amino acid. This initial discovery of a dual-use codon was labeled a duon. In humans, they discovered that about 15% of codons were dual-use codons, or duons.

This research showed that multiple overlapping or parallel codes in exons not only exist but also that these codes actually work both separately and together.1 While one set of codons specifies the order of amino acids for a protein, the very same sequence of DNA letters also specifies where necessary cellular machinery (transcription factors) are to bind to the gene to make the RNA transcript that codes for a protein.

To summarize this remarkable discovery, the researchers said, “Our results indicate that simultaneous encoding of amino acid and regulatory information within exons is a major functional feature of complex genomes,” and the “information architecture of the received genetic code is optimized for superimposition of additional information.”1

Dual Codon Codes and Translational Pausing

As an mRNA transcript copy of a gene is used to make a protein using ribosomes (located outside the cell nucleus), periodic pauses occur as the protein is produced and funneled out of a tunnel-like structure in the ribosome.2 The specific sequence and rate of pausing is critical to the folding of the protein into its proper three-dimensional shape, which occurs during the assembly process at the ribosome. Many different types of cellular machines aid in this folding process, including the ribosome tunnel through which the proteins under production pass as they are being synthesized. Because the translation and folding of the protein are linked together, the processes are called cotranslational.

In an important 2014 study elucidating the idea that codon specificity is cotranslational in its effect, researchers demonstrated that the variability in the third base of codons is nonredundant for a specific, engineered purpose.2 In this respect, it was found that specificity in the codon’s third base provides an explicit type of cellular language that is interpreted by the ribosome as telling it when to pause and how to regulate the rate at which the protein is made. This ultimately has an effect on the folding of the protein into its proper three-dimensional shape.

So, not only does a codon provide the information for which specific amino acid to add in the making of a protein, but the variant of that codon also influences the information needed to regulate its folding at multiple levels. Thus, you have two different sets of information encoded in different languages in the same section of DNA. The researchers of the translation pausing paper note, “Dual interpretations enable the assembly of the protein’s primary structure while enabling additional folding controls via pausing of the translation process.”2 What was once thought to be meaningless redundancy or wobble has now been proven to be exactly the opposite. In fact, the researchers said, “The functionality of codon redundancy denies the ill-advised label of ‘degeneracy.’”2

The authors of this research report also marveled at such obvious ingenuity and unwittingly stated their findings within the context of sophisticated intelligent design. They said,

Redundancy in the primary genetic code allows for additional independent codes. Coupled with the appropriate interpreters and algorithmic processors, multiple dimensions of meaning, and function can be instantiated into the same codon string.2

This type of jargon essentially describes a highly complex, interpretive, computer-like machine—something designed and engineered by a super-intelligent mind and certainly not the result of random processes.

Codon Codes Regulate Transcription Rates

Another discovery in 2016 showed that the third base of codons regulates rates of gene transcription, levels of mRNA copies made from a gene, and the corresponding amounts of protein produced.3 In other words, the amount of mRNA output produced from a gene is directly related to the specific DNA sequence in codons.

Gene output must be highly controlled and regulated in the cell, just like a cruise control mechanism in a car regulates its speed. If genes are not properly regulated, cellular dysfunction would result in disease or death. In addition to the many other types of DNA codes in and around genes that control transcription, now it is known that the specific sequence of codons, including the third base, plays a key role in gene regulation by controlling the rate of transcription.

Also, a specific epigenetic mark in a histone protein that the DNA is packaged with, called H3K9me3, is an interactive mechanism that contributes to the effect of codon usage on transcription. Thus, the histone epigenetic code, which I discussed in an earlier article in this series, interfaces with specific codons in genes to influence the rate of transcription.4

But what was even more amazing to the scientists that published this study was the fact that codon specificity and usage in the genome affects two entirely different, yet connected, cellular processes—transcription and translation. The authors said:

Codon usage is adapted to both translation and transcription processes; codon information is also read by the transcription machinery in forms of DNA elements, which are used to suppress or activate transcription. Although most known transcriptional regulatory elements reside in the promoter regions, our results demonstrate that the coding sequences can also play a major role in transcriptional regulation.3

Codon Codes Regulate Translation Rates

Not only do overlapping codes in codons affect transcription rates as genes are being copied into mRNAs, but they also affect translation rates (protein production). Researchers in 2018 reported another set of overlapping codon codes that control the rate of protein manufacturing at the ribosomal machinery.5

This research showed that an additional code in the third base of codons is related to the overall efficiency of the cells’ protein production. Since many proteins from many genes are made at once, the fundamental resources allocated to each type of protein are critical. One of these fundamental resources is called transfer RNA or tRNA.

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are specialized adaptor molecules composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length, that serve as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino acid sequence of proteins. The tRNAs do this by carrying a specified amino acid to the protein-synthesizing machinery—the ribosome. The complementation of a three-nucleotide codon in an mRNA by a three-nucleotide anticodon in the tRNA attached to the specified amino acid enables protein synthesis at the ribosome based on the mRNA code.

Like factories that make multiple products, all the assembly lines need a steady supply of the correct parts, and the processes involved in doing that need to be perfectly orchestrated. The tRNAs are the key parts in the protein assembly process that provide the correct amino acids at the ribosome when a protein is being synthesized. This complex coordination and resource distribution is affected by the third base in codons. Thus, the third base of a codon must be accurately coded or fine-tuned to produce the correct amount of a specified protein.

As it turns out, protein-coding genes that are highly expressed utilize optimal codons for high translation speeds, while those genes that are expressed at lower levels use codons that limit or downregulate the protein assembly process. The overall effect is that protein production in the cell becomes very optimized and efficient according to the available tRNA and amino acid resources. In fact, the authors of the paper call this overall response “proteome-wide translation efficiency,” with the term “proteome” referring to the entire protein complement of a cell at any given time.5

Conclusion

One of evolution’s main claims is that certain types of DNA sequences freely mutate and develop new functions that allow creatures to evolve, the consequences of which nature, as a mysterious agent, favors or rejects. This rather mystical concept has been traditionally applied to the protein-coding regions of genes in the third base of codons. When scientists first discovered variation in the third base of codons, they simply dismissed the variability as redundant—leading to the idea of codon degeneracy.

More importantly, they thought this alleged degeneracy was a mechanistic location in genes for evolution to occur. If the third base of a codon could be neutral to the final outcome—i.e., the third base was somewhat nonfunctional—perhaps it was free to mutate and evolve. In fact, this idea laid the foundation for what was termed the neutral model theory of evolution.6

However, this whole idea of codon degeneracy is now thoroughly debunked since at least four different layers of specified code can be embedded in a codon, including the third base. As a result, if mutations were to actually occur in the third base of a codon, the disruption of these previously unknown codes would be harmful, and thus mutations are not tolerated.

What was labeled in hopeful evolutionary ignorance as redundant/ degenerate and promoted for years as a viable mechanism for evolution has been thoroughly discredited through a series of amazing discoveries that highlight the incredible ingenuity of our Creator, the Lord Jesus Christ. As it turns out, the third base in codons cannot be randomly variable because other codes are embedded within it. One set of codes tells cell machinery (called transcription factors) that regulates the expression of genes where to bind to the DNA inside genes and can also specify the rate of mRNA transcript production. Yet another set of codon codes specifically determines the rate of protein production (translation) at the ribosomes and the proper folding of the protein as it is produced and exits the ribosome tunnel. And yet another codon code allows for amino acid resource optimization in protein production.

The human mind struggles to comprehend the overall complexity of genetic code. And now it has been revealed that many genes in their protein-coding regions have areas that contain multiple overlapping codes within the very same sequence. Even the most advanced human computer programmers can’t come close to matching the genetic code’s incredible information density and bewildering complexity. Expert human computer programmers can only write a line of code with a single directive.

An all-powerful and all-wise Creator is the only explanation for genetic code that has up to four different layers of instruction in the same sequence of information—and maybe more.

References

- Andrew B. Stergachis et al. “Exonic Transcription Factor Binding Directs Codon Choice and Affects Protein Evolution,” Science 342, no. 6164 (2013): 1367–1372.

- David J. D’Onofrio and David L. Abel, “Redundancy of the Genetic Code Enables Translational Pausing,” Frontiers in Genetics 5, no. 140 (2014).

- Zhipeng Zhou et al., “Codon Usage is an Important Determinant of Gene Expression Levels Largely Through Its Effects on Transcription,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 41 (2016): E6117–E6125.

- Jeffrey P. Tomkins, “Epigenetic Mechanisms: Adaptive Master Regulators of the Genome,” Acts & Facts, July/August 2023, 14–17.

- Idan Frumkin et al., “Codon Usage of Highly Expressed Genes Affects Proteome-Wide Translation Efficiency,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 21 (2018): E4940–E4949.

- Jeffrey P. Tomkins and Jerry Bergman, “Neutral Model, Genetic Drift and the Third Way - A Synopsis of the Self-Inflicted Demise of the Evolutionary Paradigm,” Journal of Creation 31, no. 3 (2017): 94–102.

* Dr. Tomkins is a research scientist at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in genetics from Clemson University.