When we think about human vision, the first thing that comes to mind is the eye. But just as a star football player performs with other essential players on his team, our eyes are supported by key, well-designed structures that are absolutely essential to making sight possible. We will consider some of the outer structures whose importance may get overlooked even though they are in plain sight.

For instance, eyelids are small and delicate but packed with incredible miniaturized components. Eyelids are not just floppy curtains that hang over our eyes. A small piece of dense connective tissue called the tarsal plate gives the eyelid its curved shape while also providing rigidity to its function as a movable covering (see Figure 1).

The plate is positioned near the outer edge of the eyelid, near the lashes. This is an ideal location to allow the lid to slide tightly over the globe of the eyeball. Unwanted debris is removed with every blink, much like a windshield’s wiper blades are held tightly to the glass with every swipe. And just the right amount of flexible rigidity is applied by the tarsal plates so that, upon blinking, lubricating tears are evenly spread over the eyeball.

Tarsal plates are also multifunctional. They house vital glands that produce oil-based tears for lubrication. These meibomian glands manufacture a special oil called meibum and release it through tiny ducts right at the lid margins. Tiny meibum oil droplets are captured when the lid closes. The action of the blink rolls the droplets under the lid and uniformly spreads them over the eye by the precise shape of the lid margin. Meibum is not a simple homogenous oil but actually a complicated compound of multiple oils, waxes, sterols, and esters that possess many useful properties. Meibum not only functions like man-made lubricating oils that reduce friction when two surfaces slide past each other, but also provides an oily covering over water-based tears to slow their evaporation. Human designers usually specify a rubber or wax gasket at the interface of two surfaces to make their connection waterproof. Meibum’s soft, waxy properties make the watertight seal of eyelids over our eyes possible with only mild lid pressure.

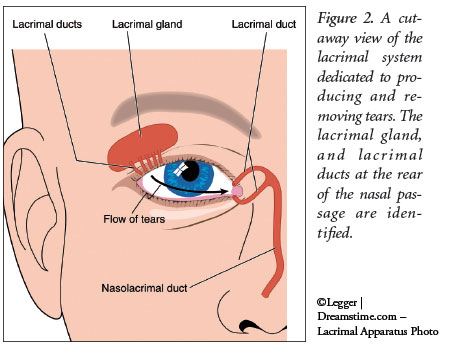

By far the largest-volume ingredient in tears is the watery liquid produced by the lacrimal gland. This liquid is vital since tears hydrate our eyes with copious irrigation. From a design standpoint, any good irrigation system would have a high-elevation water input and a lower-elevation outlet located on opposite sides of the irrigated area; that way, water would naturally flow across the area, pulled by gravity.

This is just what we find for the tears that irrigate the eye. The well-protected, indispensable lacrimal gland is shielded in the bony part of the upper orbital ring that circles above the eye and extends toward the outer part of the eye away from the nose (see Figure 2). Tears produced by this gland flow down and across the eye toward drainage ducts placed on the nasal side of the upper and lower eyelids. Generally, tear production and removal are balanced at just the right rate to not allow the eye to dry out or tears to overflow and flood down the face.

This is just what we find for the tears that irrigate the eye. The well-protected, indispensable lacrimal gland is shielded in the bony part of the upper orbital ring that circles above the eye and extends toward the outer part of the eye away from the nose (see Figure 2). Tears produced by this gland flow down and across the eye toward drainage ducts placed on the nasal side of the upper and lower eyelids. Generally, tear production and removal are balanced at just the right rate to not allow the eye to dry out or tears to overflow and flood down the face.

Just like meibum, tears also contain a variety of essential compounds. Our body usually does a great job regulating the microbes that colonize the area on and around our eyes—including some microbes that could potentially harm our eye-related structures. Tears contain mixtures of antibodies and enzymes that manage the controlled destruction of microbes. Eye infections occur when exposure to pathogenic microbes overwhelms the eye’s regulatory design parameters in terms of the numbers or types of microbes.

Another fascinating feature of tears is that only humans shed emotional tears. In times of severe emotional stress, molecules called enkephalins that are like natural opioids are released in tears. Eye tissue absorbs these molecules, and when they bind to certain receptors in the brain, the crying person may feel a sense of relief or euphoria afterward. An evolutionary story for the origin of these tears can be concocted, but a better explanation is that they are a sweet provision from a loving heavenly Father.

The outlets draining tears are rather tiny, but you can see them with the naked eye. If you look closely in the mirror, you will see a very small circular hole in each of your upper and lower lids in the angular area where the lids come together next to your nose. The openings are puncta. Amazingly, the round elevation represents an extremely small circular muscle overlaid with eyelid tissue. This structure is a remarkably efficient suctioning tear remover. Every time a person blinks, that tiny muscle contracts and closes the opening. When the lids lift, the muscle quickly relaxes, which causes a rapid re-opening. The quick opening action creates a small suction that pulls in the tears. The lower opening removes more tears than the upper one since gravity naturally draws tears toward the lower lid, where they pool.

But where do the captured tears go? Each puncta has a miniature drainpipe attached to it that conveys tears away from the eye. Just like any plumbing system, these drainage pipes, called lacrimal canals, feed into a larger pipe. In this case, it is a lacrimal duct located at the back of the nasal passage. The expended tears flow down by gravity, where they eventually drain into the back of your throat. After you swallow them, most of the watery portion is reabsorbed by your body, which means that a tiny fraction will be recycled and make its way back as fresh new tears.

The reality is that without any one of these structures, ingredients, and processes, a person would go blind. This is another wonderful illustration of how none of the primary function of vision is attained until all of the key parts are in the right place, at the right time, at the right scale, and in the right amounts. The functioning human visual system is a prime example of all-or-nothing unity and precise design. We should be thankful that we benefit so greatly from the engineering genius of our Lord Jesus Christ!

* Dr. Guliuzza is ICR’s National Representative.