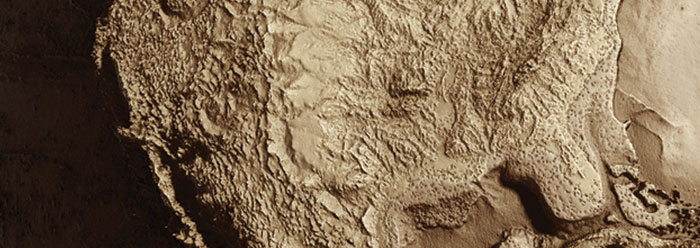

On the seminar trail, I and other ICR speakers often use Grand Canyon as an example of Flood-caused geological features. We frequently run into opposition from people who’ve been taught that it took millions of years for the canyon to be carved out. We counter with studies that lead us to believe that each of the pancake-like layers was rapidly deposited by catastrophic hydraulic forces, and that the igneous and metamorphic deposits were caused by events quite unlike anything we see in modern times. The continent-wide coverage of the layers clearly speaks to an unimaginably devastating flood. The rates, scales, and intensity of the forces involved dwarf those of our experience.

The carving of Grand Canyon itself was likewise due to rapid, dynamic erosion that either occurred late during the Flood as the continents rose, or soon afterward when immense volumes of water rushed back into the ocean basins. Furthermore, the strata give evidence of having still been in a soft, not-yet-fully consolidated condition at the time they were gouged out.

Additionally, the sedimentary layers, the volcanism, and the erosion must have occurred recently—consistent with the timescale of Scripture. The evidence indicates that the strata were deposited rapidly by Flood waters, uplifted by monumental forces later in the Flood, and eroded by retreating Flood waters before they had time to harden—all within the one-year timescale given in Genesis. ICR speakers often remark that Grand Canyon is “Exhibit A” for the great Flood of Noah’s day, and photos taken during our many research trips and study tours into the canyon’s depths frequently grace our lectures.

But if the canyon’s cause was the runoff of waters from the Flood, and the deluge was worldwide, why don’t we find many such canyons around the globe? Impressive canyons sometimes form today through natural disasters such as excessive rainfall, a dam breaking, or a tsunami event, but Grand Canyon is far bigger than these. Obviously, in any set of examples, there must always be one that is the biggest, but a fuller answer may surprise you.

Grand Canyon is unique in that erosion has exposed its remarkable stack of layers on both sides of the river, and the strata are clearly visible, not covered by vegetation. Its accessibility and stunning grandeur have earned it a place among the world’s great geological wonders. The canyon’s dimensions are staggering: 277 miles long, up to 19 miles wide, and one mile deep, but it is not the biggest canyon on Earth.

Many canyons are hidden underground or underwater, and oddly enough some are too big to see. Recent news coverage describes a hidden canyon underneath the glaciers of Antarctica. Ice-penetrating radar studies have revealed evidence that this canyon is at least 200 miles long, 15 miles wide, and two miles deep.1 Similarly, the Bering Sea between Siberia and Alaska is home to many of the largest submarine canyons in the world. An impressive canyon, often enjoyed by scuba divers, lies just offshore of San Diego. The space between England and the European continent is also a canyon, for at one time the British Isles were part of the mainland. Some consider Hudson Bay to be an Ice Age “canyon” feature. And isn’t the mid-continent space between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains a huge canyon split by the Mississippi River drainage systems? Its erosion was initiated at the end of the Flood by runoff waters and has continued throughout the Ice Age and modern calamities.

Those who believe the earth to be billions of “uniformitarian” years old occasionally consider modern rates of erosion to be greater than average. But the evidence appears to support the opposite—past processes occurring in one rapid, enormous, Earth-altering episode, just like we’re told when we go “Back to Genesis.”

Reference

- Ross, N. et.al. 2014. The Ellsworth Subglacial Highlands: Inception and retreat of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Geologic Society Bulletin. 126 (1-2): 3-15.

* Dr. Morris is President of the Institute for Creation Research and received his Ph.D. in geology from the University of Oklahoma.