A new Smithsonian exhibit will feature fleshed-out faces “of our earliest human ancestors.”1 Fossil evidence was combined with evolutionary beliefs to depict how these seven creatures may have looked. The artistic results are stunning, but are they actually historical reconstructions—or evolutionary propaganda?

The display will be exhibited at the new David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins. Paleoartist John Gurche shaped each sculpture on a cast of a fossilized skull. Careful studies of human and ape facial musculature went into his efforts. “They are perhaps the best-researched renderings of their kind,” according to a Smithsonian online report.1 No matter how well they were researched, however, the evolutionary history they depict is, at best, questionable.

The Smithsonian article captioned an image of Gurche’s sculpture of Lucy (scientific name Australopithecus afarensis) with the assertion, “below the neck, A. afarensis exhibited some human traits and could walk on two feet.”1 However, this remains a point of contention among evolutionists.

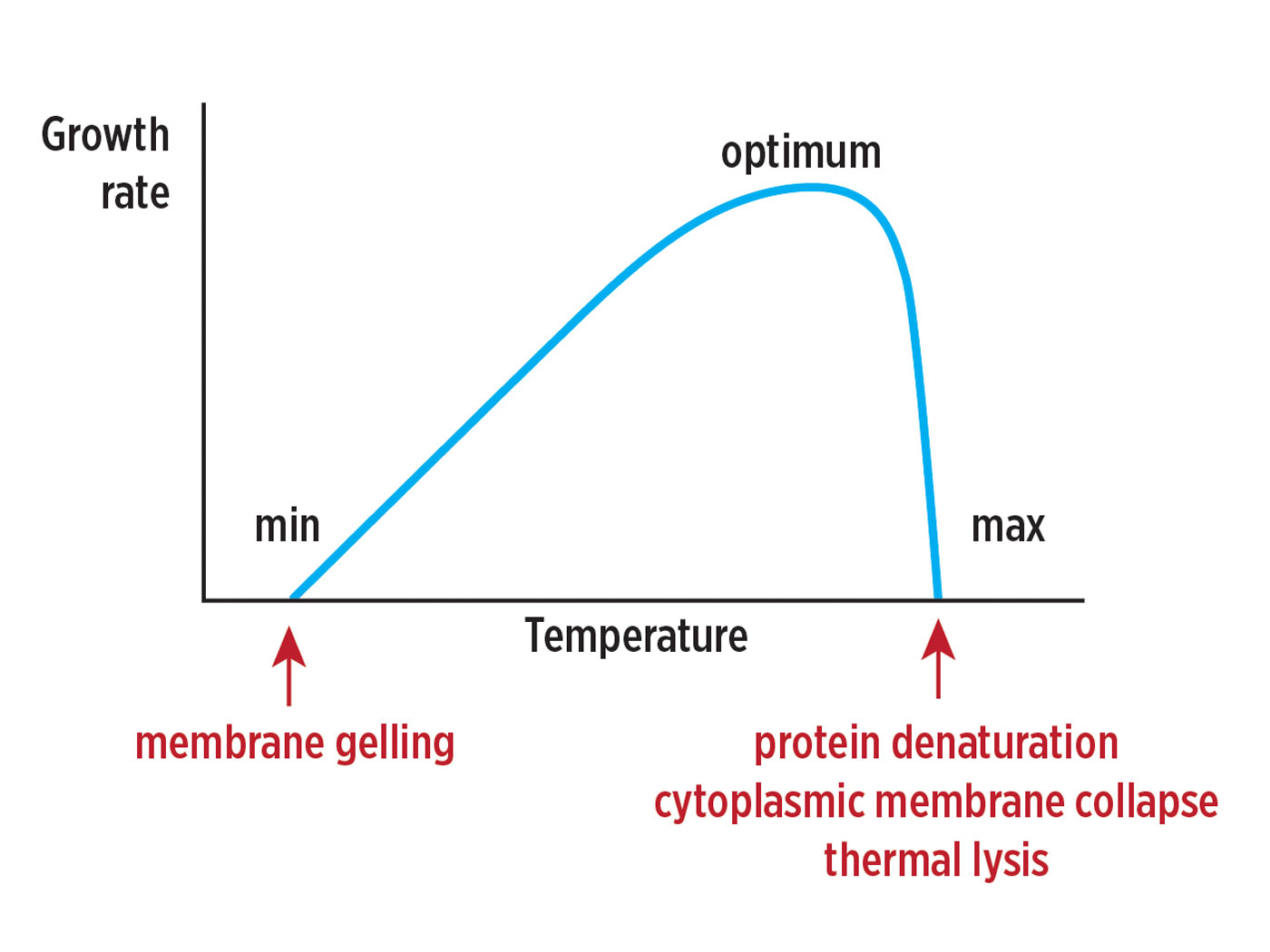

Before her hip or foot structure was known, Lucy was thought of as something like a small walking ape. The subsequent discovery that A. afarensis had tree-grasping “hands-for-feet” has not altered its evolutionary museum displays, which show Lucy in an upright, human pose that contradicts the anatomical evidence—which indicates that she did not walk at all, but was an ape that swung from tree branches.2 And if her lower body was entirely ape-like, then there is no longer any reason to include her in man’s evolutionary family tree.

Four of the seven sculptures depict various humans—Homo erectus, H. neandertalensis, H. heidelbergensis, and H. floresiensis. Since their representative fossil remains were not aligned in earth deposits according to an evolutionary sequence, the origins and relatedness of each is constantly debated. As one evolutionary writer admitted, “Everybody knows fossils are fickle; bones will sing any song you want to hear.”3

The seven sculptures, whether of ape or man, have one thing in common—Gurche put human eyes into all of them. “I wanted to get a human soul into this ape-like face, to indicate something about where she was headed,” he told National Geographic in 1996 in an article about “Lucy’s family.”4 But according to many evolutionists, Lucy was not headed toward man at all. In their view, Lucy was another evolutionary dead-end, having “emerged” only to wind up going extinct.

Gurche’s artistic choice is telling. Human eyes are distinct, not only in structure, but in function. Whereas apes and other animals detect the direction of another animal’s attention by noting the orientation of its whole head, only man notices the orientation of another person’s eyes, regardless of where the face is aimed.

Also, eye orientation is used to communicate a wide variety of thoughts and feelings from person to person. In fact, the physical structure of the whites of the eyes, the ability to detect the direction of another’s eyes, and the ability to interpret complicated expressions from that input are all required to discern meaning in a uniquely human way.

There is no scientific reason to place human eyes, which imply uniquely human thought and emotion, into ape sculptures. The only reason for that would be a desire to propagate belief in a fanciful evolutionary history of man.

References

- Tucker, A. A Closer Look at Evolutionary Faces. Smithsonian.com. Posted on smithsonianmag.com February 25, 2010, accessed March 1, 2010.

- See Wong, K. Footprints to Fill: Flat feet and doubts about makers of the Laetoli tracks. Scientific American. August 1, 2005, 18-19.

- Shreeve, J. 1990. Argument over a woman. Discover. 11(5): 58.

- Johanson, D. C. 1996. The Dawn of Humans: Face-to-Face with Lucy’s Family. National Geographic. 189 (3): 96-117.

Image credit: John Gurche

* Mr. Thomas is Science Writer at the Institute for Creation Research.

Article posted on March 12, 2010.