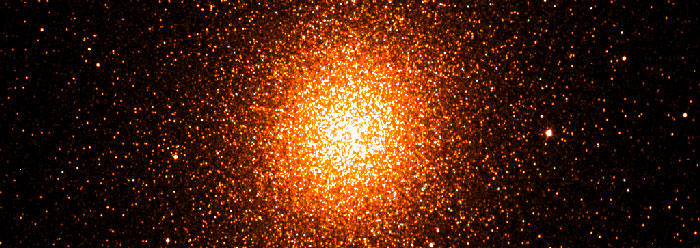

Some of the most stunning astronomical objects are globular clusters. These spherically-distributed celestial ornaments can pack a million stars within a tiny angle of space as seen from Earth. For example, M13 in Hercules fills the eyepiece of a 14" Schmidt-Cassegrain or 20" Dobsonian telescope. Omega Centauri, better placed for southern-hemisphere observers, is the largest globular of our galaxy and one of the few visible with the naked eye.

Stars in a globular appear densely packed but are actually widely spaced. About 180 of these clusters orbit the center of the Milky Way at various inclinations, and globulars have also been detected around other galaxies. They have played an important role in the development of astronomical thought since the Christian astronomer William Herschel named them in 1789. Few amateurs at star parties may know that they are now centerpieces of a significant upset in astronomy occurring right now, after a near century of consensus.

In 1914, Harlow Shapley noticed their spectra were different from those in the galactic disk. He named the disk stars Population I, and the globular cluster stars Population II. Because they are low in elements heavier than helium, the Population II stars were assumed to be older than the Population I stars. (A third category, Population III, is assumed to comprise the very first stars after the Big Bang, made out of pure hydrogen and helium, but none have been observed.) The distinct spectral signature of globulars, combined with their lack of dust and gas, gave rise to the view that they represent some of the oldest objects in the universe, mostly composed of old red giants in regions where no new stars are forming. The disk, by contrast, was thought to be young and actively engaged in star formation. This had been the textbook orthodoxy for most of the twentieth century.

The story started to unravel three years ago (see Astronomy, Nov. 2003) when the Hubble and other orbiting telescopes found globulars containing mixed populations of stars, with exotic members called "blue stragglers" and even planets. News@Nature last August reported that the findings are "changing our ideas completely" and will require us to "tear up textbooks." New explanations are being considered. Perhaps they formed during galactic mergers. But each new solution breeds new problems: how was there enough material left over to form these densely-packed clusters?

One thing is clear; globulars can no longer be thought of as simple, homogeneous collections of ancient stars. The article said, "In a complex Universe, astronomers thought they had at least one simple system to tell them how stars are born. Turns out they were wrong." Moreover, this upset can have ripple effects on other theories. One astronomer said, "If you have problems reproducing star formation in globular clusters, you will have problems with a galaxy."

Astronomers will undoubtedly come up with new ideas. There's an important lesson here about how science is done in these days of Big Bang-to-man theorizing. It's not that scientists are unable to concoct a story to fit the data, it's that the data require a story to fit a belief.

*David F. Coppedge works in the Cassini program at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Cite this article: Coppedge, D. 2007. The Globular Cluster Bomb. Acts & Facts. 36 (2).