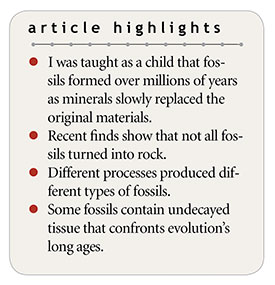

I picked up my first fossil from beneath a swing in Kansas when I was six years old. Fossils have fascinated me ever since. Soon after, our family visited a dinosaur museum. The nice lady there explained that dinosaur fossils are actually rocks in the shape of bones. After all, she said, the process of fossilization takes millions of years. Over that much time, minerals would fully replace all the original bone. That sounded fine, so I believed it.

I picked up my first fossil from beneath a swing in Kansas when I was six years old. Fossils have fascinated me ever since. Soon after, our family visited a dinosaur museum. The nice lady there explained that dinosaur fossils are actually rocks in the shape of bones. After all, she said, the process of fossilization takes millions of years. Over that much time, minerals would fully replace all the original bone. That sounded fine, so I believed it.

Decades later, I saw pictures that challenged all that. Published in the journal Science, color photographs showed blood-red flesh with white, flexible connective tissue from inside a T. rex leg bone.1 Wow, that’s not rock. I was taught to think that water carried dissolved minerals through tiny holes deep into bones. The water went away and left the minerals behind in a process called permineralization. It did happen that way for many fossils—but not all.

Scientific evidence of soft, flexible, original biomaterial from this and scores of similar finds from around the world forced me to rethink the meaning of “fossil.”2 It turns out that different fossils formed in different ways. Some fossils are mostly mineralized, but others look like dried-out carcasses.

Some creatures got flattened and heated beneath tons of sediment. Later processes brought them back to Earth’s surface in places like Canada’s Burgess Shale. There, researchers peel apart thin mudstone sheets to reveal blackish residues—all that’s left of ancient sea creatures. The heat and pressure baked original biomaterials including proteins and sugars into the black, carbonized material we find today.

Other fossils show mineral outlines of original soft organs like brains or guts. As creatures decayed inside drying mud, bacteria clung to the outer surface of each organ. The bacteria made chemical waste products that attracted nearby sulfur, iron, or phosphorus. Today, we see organs outlined in yellows and reds from bacterial-influenced sulfurization, pyritization, or phosphatization. In these cases and others, longer-lasting minerals replaced the original biomaterials.

I felt new shock when I read a study of original biomaterial in Burgess Shale sea sponge fossils. Not rock, not mineral, not phosphatized, not blackened, but sponges with original proteins and carbohydrates intact. Perhaps these sponges landed in a spot that didn’t get quite as hot. Secular scientists insist they were buried 505 million years ago,3 but nobody has shown any biomaterial with properties that would allow it to last much longer than a mere one million years. This means they could have lasted for the thousands of years since Noah’s Flood buried them but not for the millions of years that so many people claim.

A growing number of fossils look virtually unchanged, and these original biomaterial fossils confront evolution’s long ages. ![]()

So, what does fossilize mean? Different fossils show different origins. Some were replaced with mineral, like the nice lady at the museum said. Others show mineral outlines of original organs or carbon films from baked bodies. But a growing number of fossils look virtually unchanged, and these original biomaterial fossils confront evolution’s long ages.

References

- Schweitzer, M. H. et al. 2005. Soft-Tissue Vessels and Cellular Preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex. Science. 307 (5717): 1952-1955.

- Thomas, B. 2013. A Review of Original Tissue Fossils and Their Age Implications. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. M. Horstemeyer, ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship.

- Ehrlich, H. et al. 2013. Discovery of 505-million-year old chitin in the basal demosponge Vauxia gracilenta. Scientific Reports. 3: 3497.

* Mr. Thomas is Science Writer at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his M.S. in biotechnology from Stephen F. Austin State University.