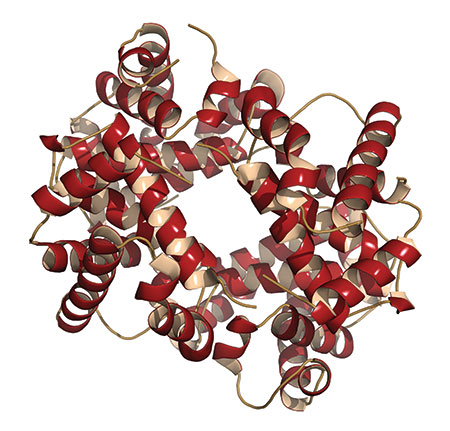

Hemoglobin is an iron-containing respiratory protein in red blood cells that binds oxygen and then transports and releases it to cells that need oxygen. It’s designed as four subunits (two alpha and two beta chains), each with an eight-helix folded pattern. This configuration enables conformational changes of the protein so that oxygen molecules can easily load and unload. God has designed hemoglobin in a wide range of His creatures, both invertebrates (arthropods, mollusks, annelids, and echinoderms) and vertebrates.

Hemoglobin is an iron-containing respiratory protein in red blood cells that binds oxygen and then transports and releases it to cells that need oxygen. It’s designed as four subunits (two alpha and two beta chains), each with an eight-helix folded pattern. This configuration enables conformational changes of the protein so that oxygen molecules can easily load and unload. God has designed hemoglobin in a wide range of His creatures, both invertebrates (arthropods, mollusks, annelids, and echinoderms) and vertebrates.

Hemoglobin has always been hemoglobin—there’s no evidence it evolved. ![]()

Did hemoglobin evolve? Evolutionists should be able to trace how this amazing protein molecule originated—but they can’t. Scientists have no fossil molecules, and thus they cannot go back into deep evolutionary time and analyze the hypothetical pre-hemoglobin that supposedly existed. Evolutionists Richard Dickerson and Irving Geis stated that hemoglobins are “a puzzling problem. Hemoglobins occur sporadically among the invertebrate phyla in no obvious [evolutionary branching] pattern.” Dickerson goes on to say, “It is hard to see a common line of descent snaking in so unsystematic a way through so many different phyla.”1

A decade later, another evolutionist said:

Who would consider seriously a phylogeny of vertebrates drawn from a comparison of myoglobin [a single polypeptide chain molecule found in the muscles of vertebrates] of some species and hemoglobin from others? The species for which myoglobin is used will cluster together far away from the related species for which hemoglobin is selected....The main problem here is the reliability of evolutionary reconstructions based on sequence data....The composite evolutionary tree...encompasses all the weaknesses of the individual trees.2

The fact is that whenever hemoglobin is found in the living world, it’s always fully functional and completely optimized to the needs of the specific creature in which it resides. In a recent report, Sjaak Philipsen and Ross Hardison wrote:

While the full physiological significance of the developmental diversity of hemoglobins is not yet understood, it is clear that the multiplicity of hemoglobins produced in a developmentally controlled manner is a strongly conserved feature across vertebrates, including the jawless vertebrates (agnathans), which are the most distantly related extant vertebrate relatives to humans.3

When Philipsen and Hardison use the phrase “strongly con-served,” they are simply saying the hemoglobins somehow remained unchanged over the large expanses of presumed evolutionary time. Hemoglobin has always been hemoglobin no matter where it is found. For example, many deep-ocean trenches have hydrothermal vents that constantly stream superheated mineral-rich water. The vents provide the heat and nutrients to sustain a range of biodiversity that includes large, bizarre tube worms (genus Riftia). These annelids are designed with bright-red plume structures. The red color is from several complex hemoglobins that have 144 globin chains. “The high molecular mass hemoglobin of the worm is the transporter for both oxygen and sulfide.”4 The worms have an amazing extracellular multi-hemoglobin system with one in the coelomic cavity (a fluid-filled body cavity) and two in the vascular (blood system) compartment.5

Evolutionists generally refer to an unknown evolutionary ancestor to explain ancestral states. In a study on vertebrate globins, Jay Storz and his colleagues wrote, “The retention of the proto-Hb and Mb genes in the ancestor of jawed vertebrates permitted a physiological division of labor between the oxygen-carrier function of Hb [hemoglobin] and the oxygen-storage function of Mb [myoglobin].”6

Storz et al appeals to an alleged ancestor of jawed vertebrates—but such an ethereal creature has never been found in the fossil record. Nor is there agreement on what that ancestor should or would be.

Features of the most recent common ancestor of all bilaterian animals have been much debated.7

Faced with these intrinsic obstacles and with little evidence from the fossil record to help, it is hardly surprising that disagreement over the origin of chordates [a phylum containing amphioxus, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals] has been common.8

The hemoglobin molecule is designed with much variation to supply the oxygen needs of a wide variety of organisms. There are over 300 alleles (one of two or more forms of a gene that produce variations in a given trait) for the hemoglobin gene, part of the globin gene superfamily. Secular scientists attempt to explain their origin using terms such as duplication (a form of mutation that overwhelmingly destroys genetic information) and translocation.

Comparative studies also have been conducted on the genes and gene clusters that encode the hemoglobins, revealing a rich history of gene duplications and losses as well as translocations.9

The functional diversification of the vertebrate globin gene superfamily provides an especially vivid illustration of the role of gene duplication and whole-genome duplication in promoting evolutionary innovation.10

But is this large family the product of random duplications resulting in functional diversification? The concept of duplication and divergence is a cornerstone of neo-Darwinism. Evolutionists often appeal to gene duplication, a process in which a gene is somehow accidentally copied. In the ideal evolutionary world, one copy remains the same by “purifying selection” while the other copy supposedly becomes a “new” gene that is unaffected by purifying selection and magically evolves a new function.

The problem is that any gene will have accumulated mutations throughout evolutionary time. It is not in a pristine state. A duplication of that gene will have the mutations duplicated with it. Indeed, both copies will still degenerate. When a gene duplication occurs, it negatively affects its own expression (the production of protein or regulatory RNA), not to mention the expression of other genes.11 Storz et al also appeal to whole-genome duplication, but this is even more problematic, if not lethal. Whole-genome duplication is also called polyploidy, the condition in which an organism possesses one or more sets of chromosomes in excess of the normal two sets. Polyploid plants are common, but duplicating the human genome would be fatal. Ironically, evolutionists suggest that “initial genome duplications, estimated to have occurred at least 600 million years ago, shaped the genome of all vertebrates.”12

This was never observed, of course, but is based on theoretical speculation or assumption, as the times of the duplication events of vertebrate globin genes can only be inferred.13 Evolutionist Douglas Futuyma states:

The origin of hemoglobin and myoglobin from a common ancestral gene occurred in the ancestor of all vertebrates, but the alpha and beta hemoglobin subfamilies originated by duplication in an ancestor of the jawed vertebrates.14

Evolutionists assume the “ancestor of the jawed vertebrates” was a branch of the placoderms (“ancient” heavily armored fish) that gave rise to the present-day gnathostomes, a superclass that includes 99% of all living vertebrates. One should keep in mind, however, that “zoologists do not know what animals were the first vertebrates.”15

Storz et al call on the mystical non-explanation of convergent evolution to describe how different creatures end up with related purposeful specializations:

Phylogenetic and comparative genomic analyses of the vertebrate globin gene superfamily have revealed numerous instances in which paralogous globins have convergently evolved similar expression patterns and/or similar functional specializations in different organismal lineages.16

Evolutionists commonly call upon convergence when similar expression patterns are seen in different lineages. But in these cases, it’s more of a declaration based on expectation than an actual observation. Creation biologist Gary Parker notes:

Convergence, in the sense of similar structures designed to meet similar needs, would be expected, of course, on the basis of creation according to common design.17

Perhaps one of the more striking cases for creation is the unique structures of hemoglobin found in the early stages of human development—in the last seven months of the fetus’ growth in the womb up to the approximate age of six months after birth. The structures are called embryonic (there are three types) and fetal hemoglobin (HbF), and they differ from adult hemoglobin (HbA) in that there are changes in the hemoglobin chains.18

In what is seen as good engineering by the Creator, embryonic and fetal hemoglobins have a greater affinity for binding oxygen than adult hemoglobin. This means the developing baby receives critical oxygen from the mother’s bloodstream, and the various hemoglobins under the changing conditions during development can in turn release the oxygen into the baby’s tissues. Another remarkable fact is that hemoglobin is first made in a special structure aligned with the umbilical cord called the umbilical vesicle and is produced in the liver and spleen, and then finally in bone marrow after bones develop. This phenomenal system has to have been designed.

Hemoglobin is yet another of God’s great designs. ![]()

Neither organisms nor their globins evolved through blind chance and long time periods. Instead, the “different organismal lineages” were recently created and utilize these globins based on their niche in the environment. Creationists look at the origin, structure, and placement in the living world of the incredible hemoglobin molecule and see the hand of the all-wise Creator.

References

- Dickerson, R. E. and I. Geis. 1969. The Structure and Action of Proteins. New York: Harper & Row, 72.

- Demoulin, V. 1979. Protein and nucleic acid sequence data and phylogeny. Science. 205 (4410): 1036-1038.

- Philipsen, S. and R. C. Hardison. 2018. Evolution of hemoglobin loci and their regulatory elements. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 70: 2-12.

- Minic, Z. and G. Hervé. 2004. Biochemical and enzymological aspects of the symbiosis between the deep-sea tubeworm Riftia pachyptila and its bacterial endosymbiont. European Journal of Biochemistry. 271 (15): 3093-3102.

- Zal, F. et al. 1996. The Multi-hemoglobin System of the Hydrothermal Vent Tube Worm Riftia pachyptila. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (15): 8869-8874.

- Storz, J. F., J. C. Opazo, and F. G. Hoffmann. 2013. Gene duplication, genome duplication, and the functional diversification of vertebrate globins. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 66 (2): 469-478.

- Hickman, C. H. et al. 2011. Integrated Principles of Zoology, 15th ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw Hill, 307.

- Kardong, K. V. 2012. Vertebrates, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 74.

- Hardison, R. C. 2012. Evolution of Hemoglobin and Its Genes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2 (12): a011627.

- Storz, Gene duplication.

- Gauger, A. K. and D. D. Axe. 2011. The Evolutionary Accessibility of New Enzyme Functions: A Case Study from the Biotin Pathway. BIO-Complexity. (1): 1-17.

- Vandepoele, K. et al. 2004. Major events in the genome evolution of vertebrates: Paranome age and size differ considerably between ray-finned fishes and land vertebrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (6): 1638-1643.

- Hardison, Evolution of Hemoglobin and Its Genes, Figure 1.

- Futuyma, D. J. 2013. Evolution, 3rd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 73.

- Miller, S. A. and J. P. Harley. 2013. Zoology, 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 331.

- Storz, Gene duplication.

- Parker, G. 2006. Creation: Facts of Life. Green Forest, AR: Master Books. 46.

- Sankaran, V. G. and S. H. Orkin. 2013. The Switch from Fetal to Adult Hemoglobin. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 3 (1): a011643.

*Mr. Sherwin is Research Associate, Senior Lecturer, and Science Writer at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his M.A. in zoology from the University of Northern Colorado.

Image credit: vodolaz/Bigstock.com. Used in accordance with federal copyright (fair use doctrine) law. Usage by ICR does not imply endorsement of copyright holder.